"Injured images"

in the Ullstein photographic collection

Interview with Anton Holzer | Editor Fotogeschichte, Vienna

About the traces on photographs in the ullstein bild collection. Interview with Anton Holzer, photo historian, author and editor of the magazine Fotogeschichte – Beiträge zur Geschichte und Ästhetik der Fotografie

_______________________________________________________________

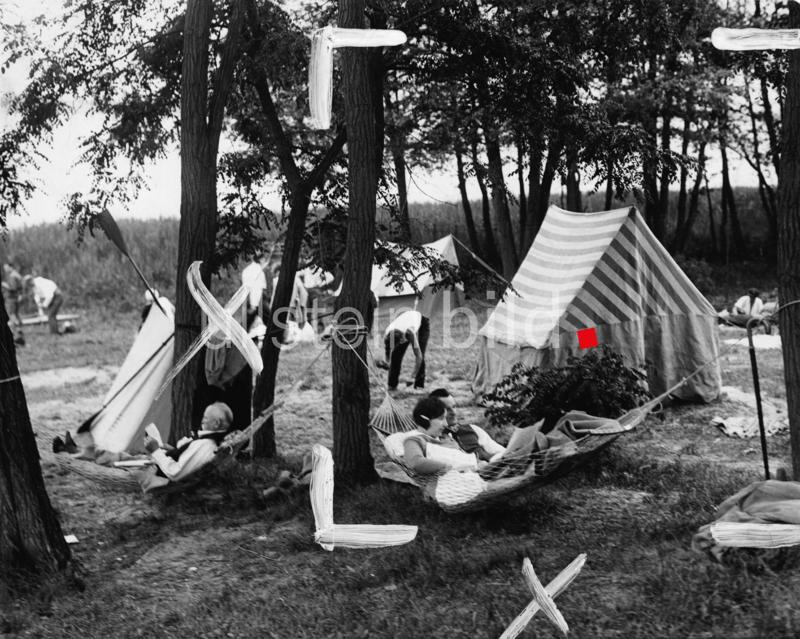

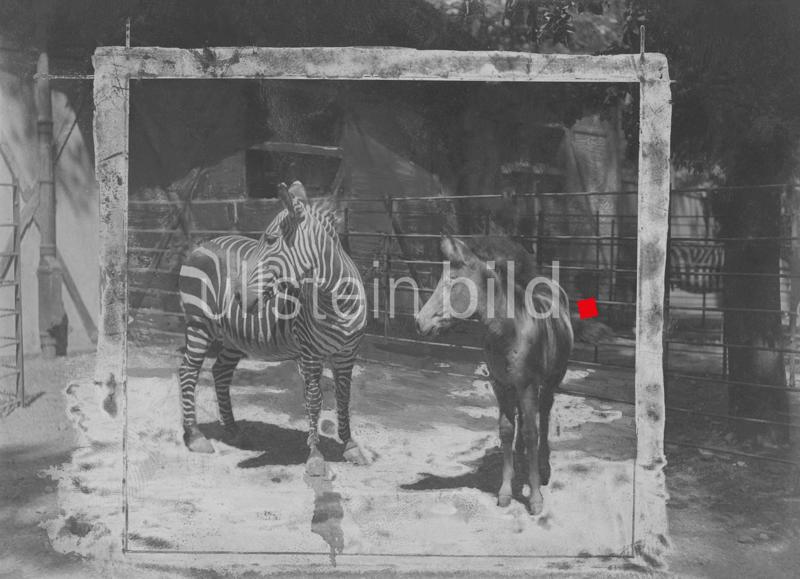

Injured images – a fascinating and important topic for a collection such as the Ullstein photographic collection, which has been growing steadily since the turn of the 20th century. If images convey stories, then photographs that bear clear traces certainly do this too, and even more so. Traces that their viewers cannot expect. They have various causes: Use, decay, external climatic influences, carelessness, but also deliberate intervention and alteration. These traces raise questions: What conditions and what technique are behind them? Which pictorial elements are they aimed at? What are the intentions behind the intervention? What is the historical context of the changes?

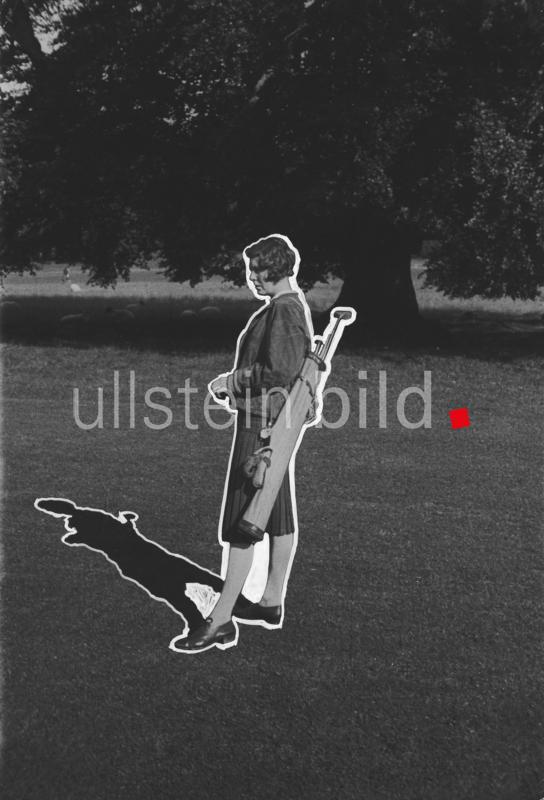

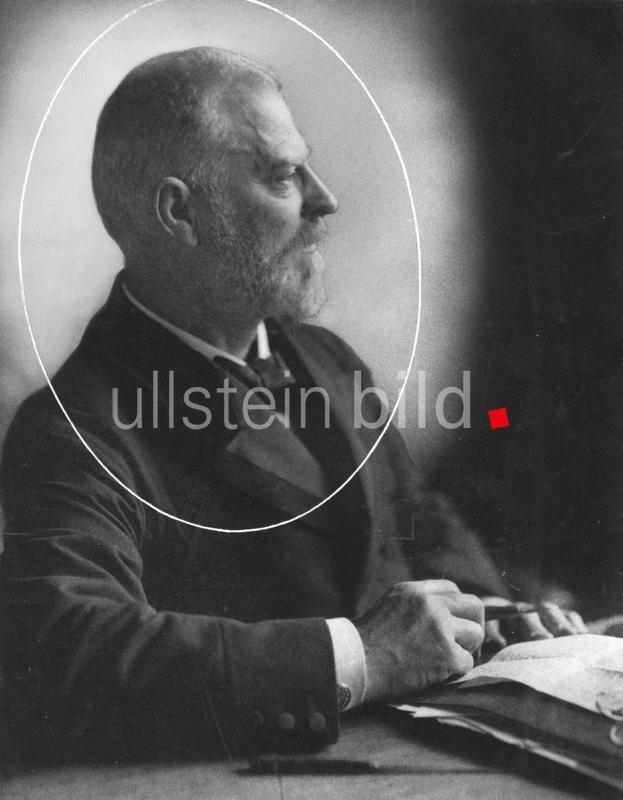

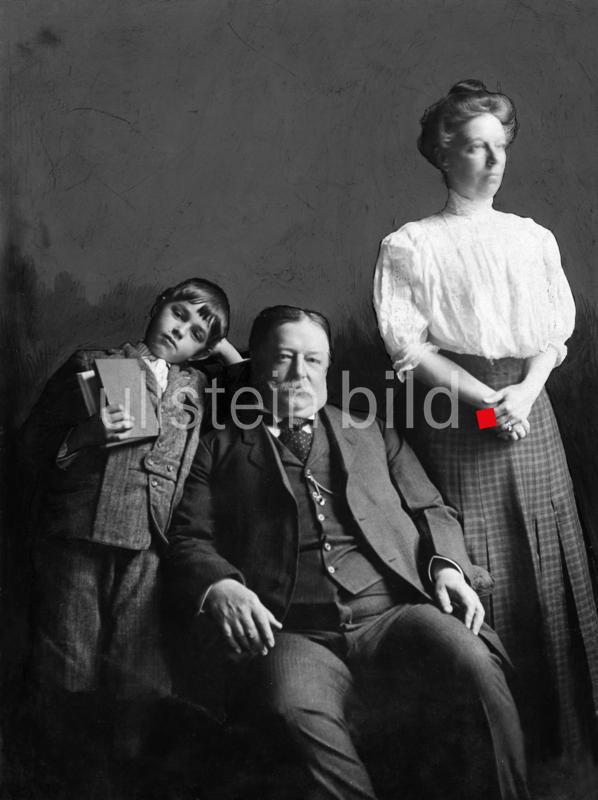

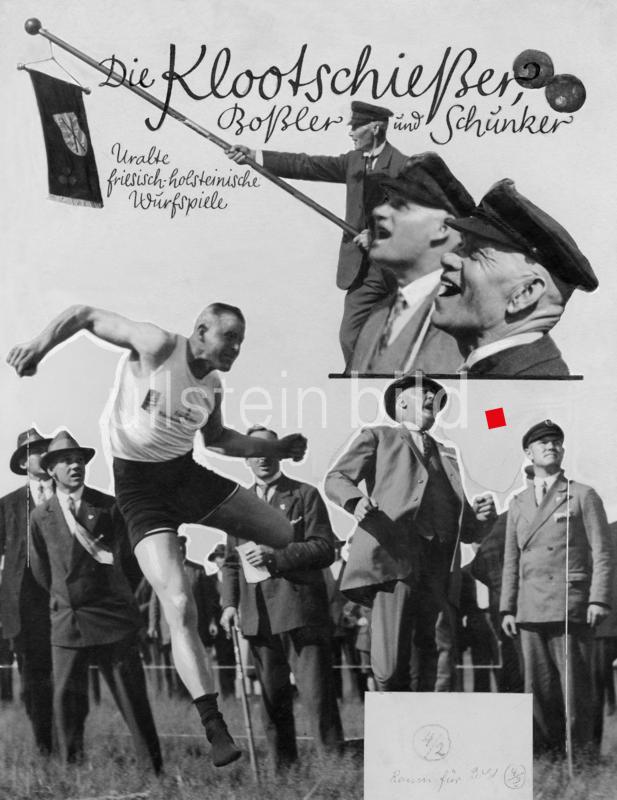

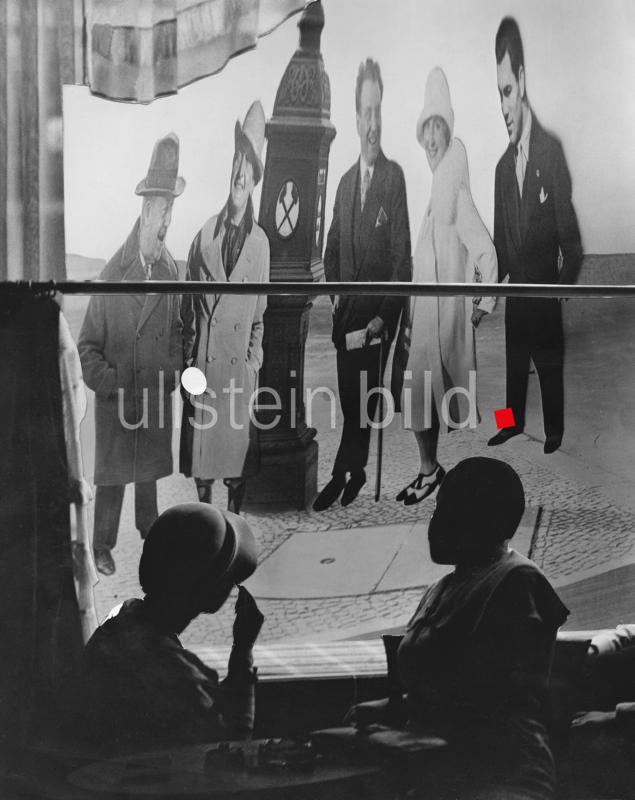

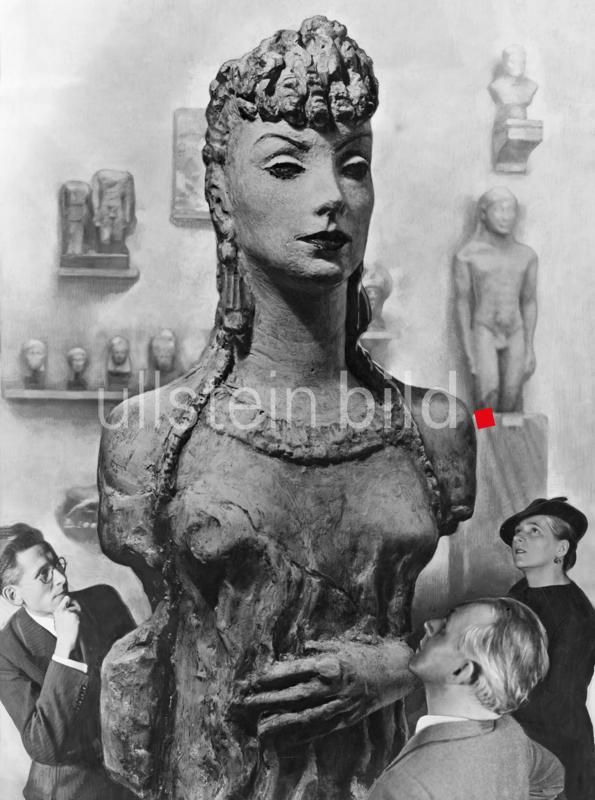

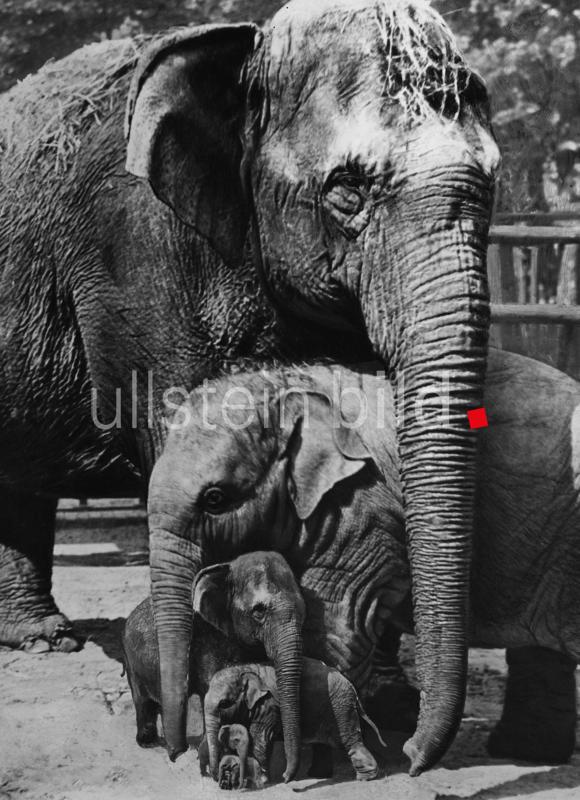

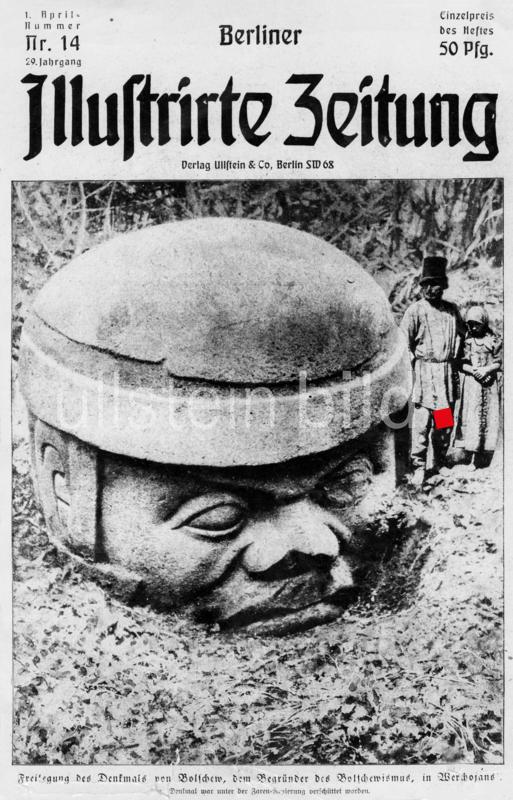

The image examples in the gallery below give an impression of the range of cases. Without exception, these are original photographs that were used as artwork at the time and are in an editorial context. It is about press photography. Emphasis and reduction are equally the theme. The billows of smoke from the November Revolution of 1918 and the rising cigarette smoke in the portrait of the artist Anders Zorn from 1913 were emphasized in the drawings so as not to withhold them from the readers of the Ullstein newspapers and magazines in the print, to strengthen their effect – or to obscure other parts of the picture.

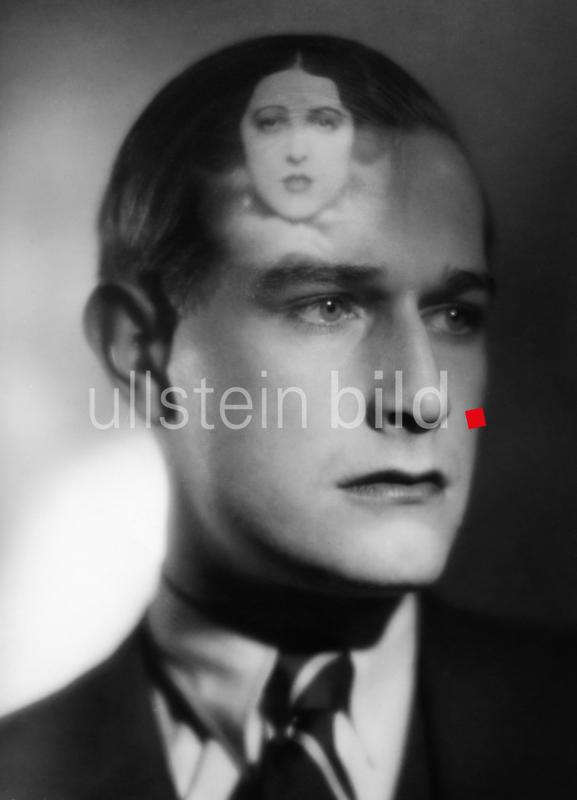

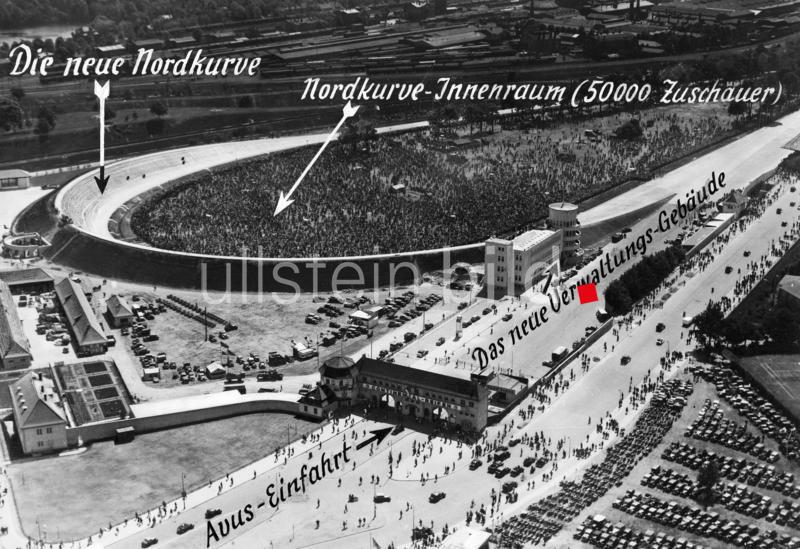

In many of the motifs, one suspects that the popularity and importance of the subject led to direct intervention in the photography. In the portrait of Archduke Friedrich of Austria by A. & E. Frankl, all the bystanders in the scene have to be retouched out so that the reproduction in the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung in 1915 can concentrate on the person of the Archduke.The famous shipowner and politician Adolph Woermann, whose half-portrait was cropped in 1911 to create a medallion in a format suitable for publication in the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, suffered a similar fate. And, of course, the jewelry of a sensational dancer like Anita Berber had to be emphasized by drawing on the photograph so that these attributes remained recognizable in the publication. The treatment of the cover pictures is also characterized by their special nature. Some of the photographs by Martin Munkácsi, who worked successfully for Ullstein for a long time, were designed for a large-format effect and were used accordingly. In 1929, for example, the lettering of the Berliner Illustrirte could be mounted in the photographed crowd for the title page, while at the same time receding into the background as a set piece: an expression of the awareness of the decisive effect of an image and the creative use of photography.

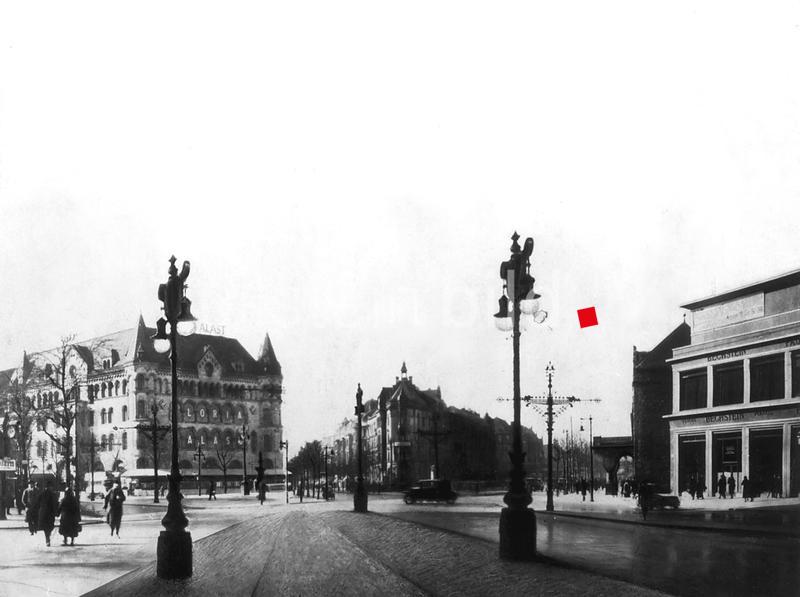

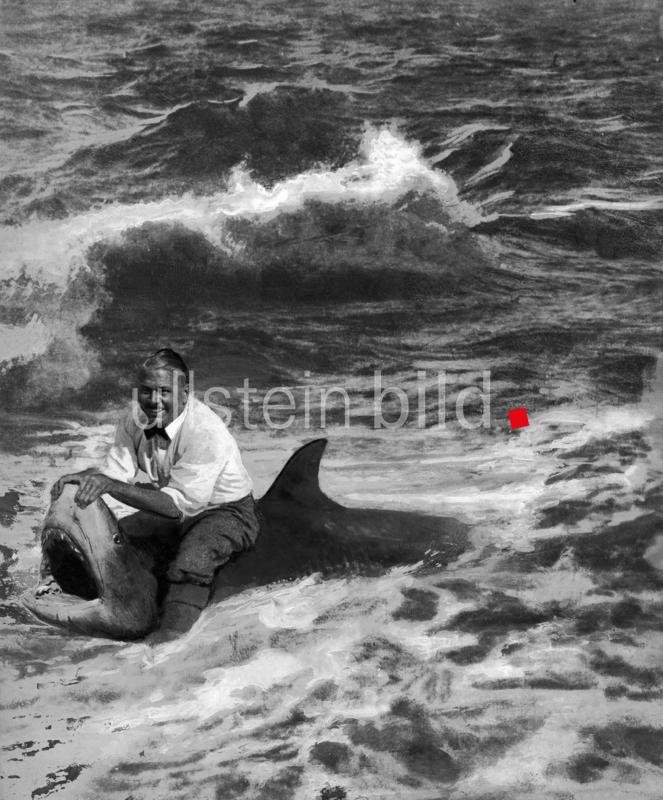

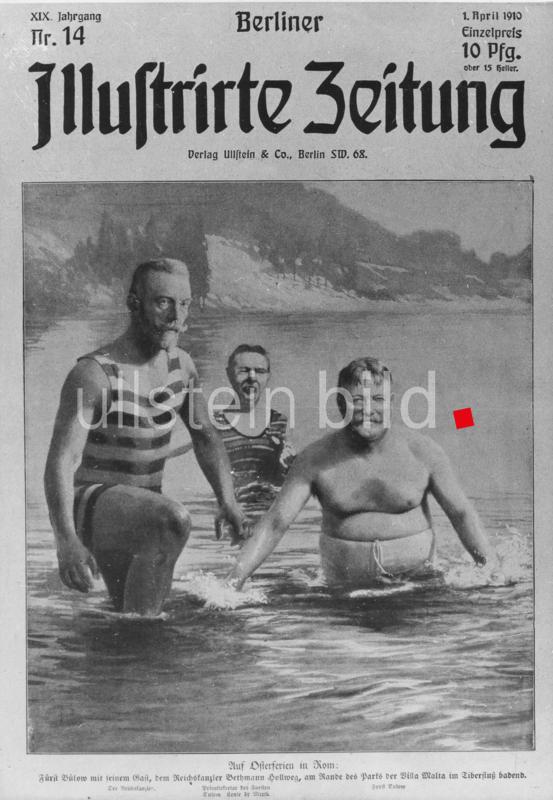

But there are also other ways of altering the original image motif. These include the categories of April Fool's jokes and prize puzzles published in the Ullstein titles. Friedrichstrasse under water as the "Grand Canal" of Berlin (around 1900), the ride on the shark (1924), eight generations of elephants in a photo by Friedrich Seidenstücker (1932), Thomas Mann as a car driver (1931), and Prince Bülow, Conte de Menti and Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg bathing in the Tiber (1910) - none of them would have been possible without photomontage and retouching.

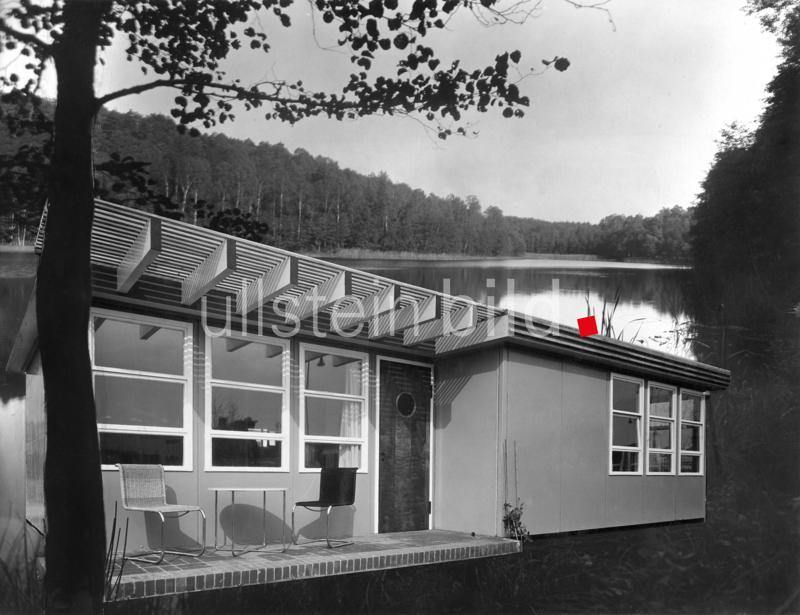

What if? This question does not stop at photography, for example when Berlin architecture is the subject. Max Taut's growing house was photomontaged into a lake landscape in 1932. The montage on a Sasha Stone photograph from 1926 shows what Kaiserin-Augusta-Platz would look like without the Gedächtniskirche: very tidy.

Speaking of Sasha Stone. In contrast to the photomontage mentioned above, a photograph published in UHU in 1926 shows concentric circles, numbers, words and characters over the entire surface of the reportage Das hundertpferdige Büro (The Hundred-Horse Office) in order to increase the effectiveness of the photograph and make use of the expressive possibilities of modernism. The caption speaks for itself: the 'Memor' memory clock uses an alarm clock to remind us of all the agreements and conferences made at various times during the day. In our interview on New Objectivity and the corresponding exhibition at the Centre Pompidou 2022, Florian Ebner pointed out the significance of this exhibit and this reportage.

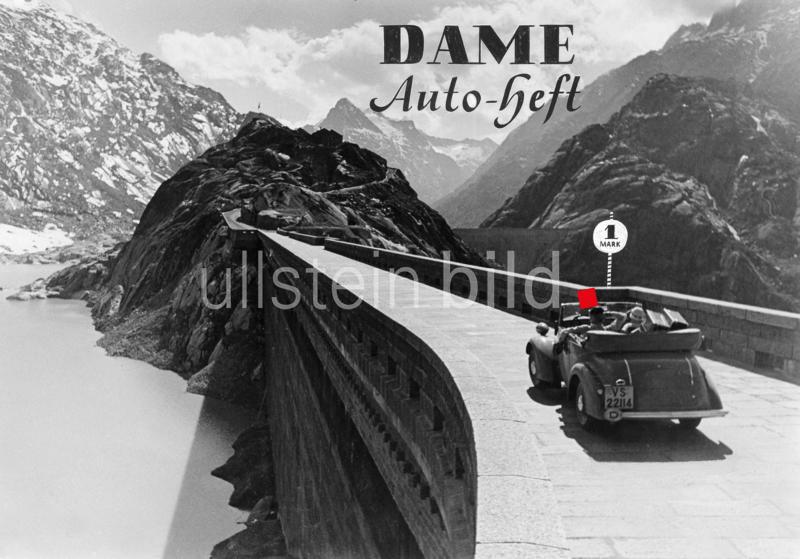

The labeling of the photograph can also have more mundane, less modern-looking reasons. To identify places and people, to convey explanations, to illustrate contexts – to direct perspectives. And not to forget: to advertise. Lettering and image come together in a photograph by Paul Wolff in 1935 to maneuver the viewer directly into the publication via the attractive road layout in the Swiss mountains and to interest them in this special issue of the Ullstein magazine Die Dame.

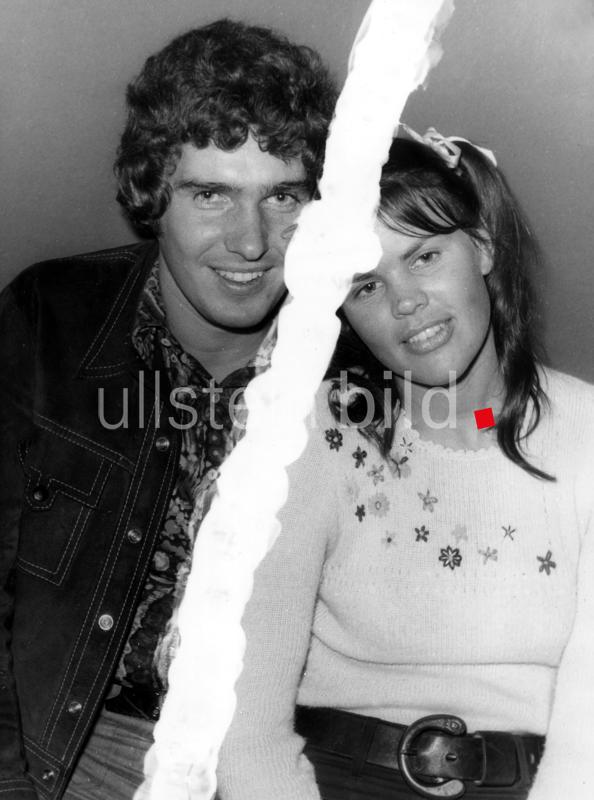

Emotions also play a major role in the publication's approach to photography. Moving events such as marriages and separations are not left uncommented. For the marriage of celebrities such as Gustav Gründgens and Marianne Hoppe in 1936, the two profile shots by photographer Rosemarie Clausen were mounted to illustrate the couple in large format and in decisive proximity to each other.The serial montages by photographer Karl Schenker were created a few years earlier. They served to portray the young couple Gottfried von Cramm and Elisabeth von Dobeneck and, even more importantly, to artistically stage their togetherness. The photo was consequently published as the cover picture in 1932. A few decades later, the clear retouching of a strong dividing line between pop singer Frank Schöbel and Chris Doerk in a 1975 photograph by Friedhelm von Estorff demonstrates just how harsh the opposite can be. The rift between football player and coach Heinz Höher and manager Herrmann Gerland in 1989 is also symbolized by a jagged line of retouching.

If the author of the image himself intervenes, there are good reasons for this: a contact print from the Haeckel collection was vigorously crossed out in pencil several times, probably as an expression of dissatisfaction or as a warning. When archivists become radical, a dilemma arises: handing over a photograph from around 1919 to the paper perforator ends in disaster - the damage remains irrevocable. The traces of use of a photograph that has passed through many hands and been sent several times on reproduction routes are comprehensible. Haste or improper storage can do the rest.

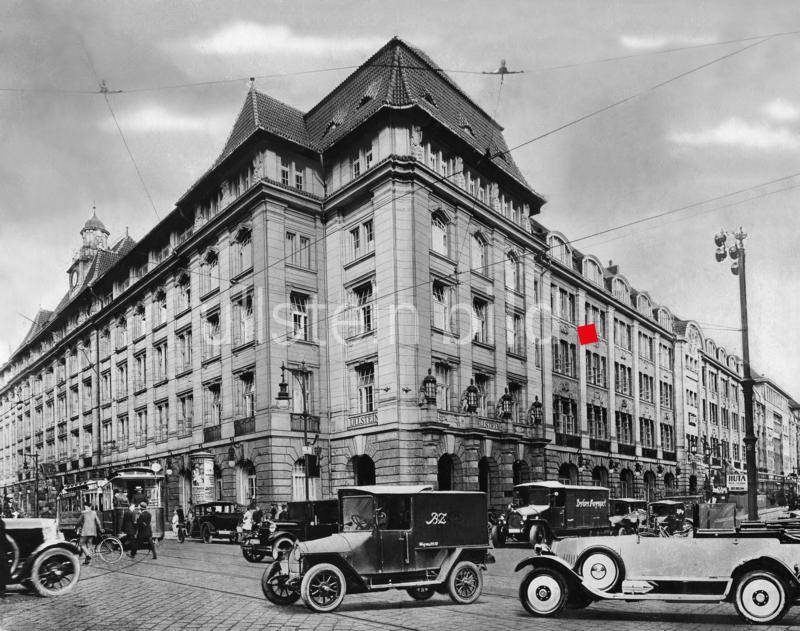

However, it becomes more interesting when the statement or origin of the photograph is to be changed. These measures mainly affect the backs of the photographs. In addition to the written request for retouching and editing, there is space here for entire reinterpretations, highlighting or negations: How many times was the name of Ullstein Verlag blacked out beyond recognition on the back or overstamped with "Deutscher Verlag" – the years of press work under National Socialism, one could say: the infamous exploitation of the Ullstein collection left its mark.

The caption on the back of the photo can also clearly contradict the photograph: misidentification, false attribution, contradictory statements are just some of the possibilities. And every now and then a question mark behind a note exercises restraint.

While image authors such as Yva, Sasha Stone, Martin Munkácsi and Karl Schenker used photography as an art form, various alterations and interventions document the historical use of photography. They can be very different, both in terms of the quality of the execution and the intention. Within a collection as rich and deeply rooted as the Ullstein photographic collection, it will always speak of the conditions and possibilities at the time of its creation – with consequences for a widely effective press world.

Mr. Holzer, the current issue 171/2024 of the magazine Fotogeschichte, which you edit, is entitled Injured Images. You describe the often lacking consideration of this topic in the history of photography and clarify: "From the very beginning, photography was far removed from the perfect, transparent image." How can this contradiction be resolved, do we need rethought photo exhibitions?

To a certain extent, I suppose so. Of course, museums and publishers want to show the best possible pictures, but some photographs are much more meaningful if the traces of their use are not ignored, but clearly shown. Most historical photos have come a long way before they become museum-worthy. Perhaps they were initially privately owned, in a shoe box, in an attic, wrapped in plastic, who knows. They were picked up, hung up, put away. All these activities, places and paths have left traces. The museum context tends to erase or cover them up. However, it is often important to reveal the contradictions between use and musealization.

How do you assess the topic of "violated images" on the basis of Ullstein's press photo collection in Berlin, which is also relevant in this respect?

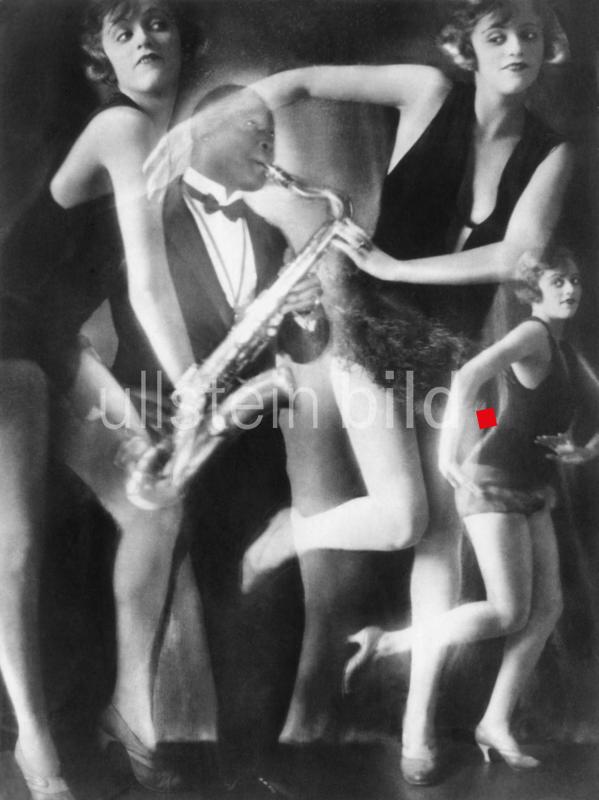

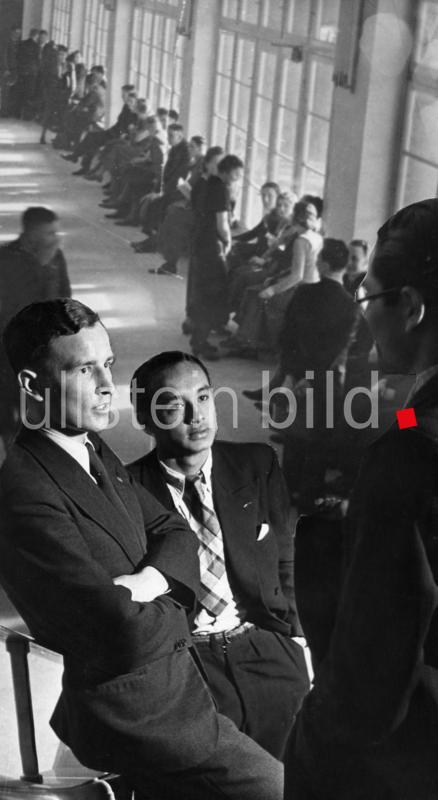

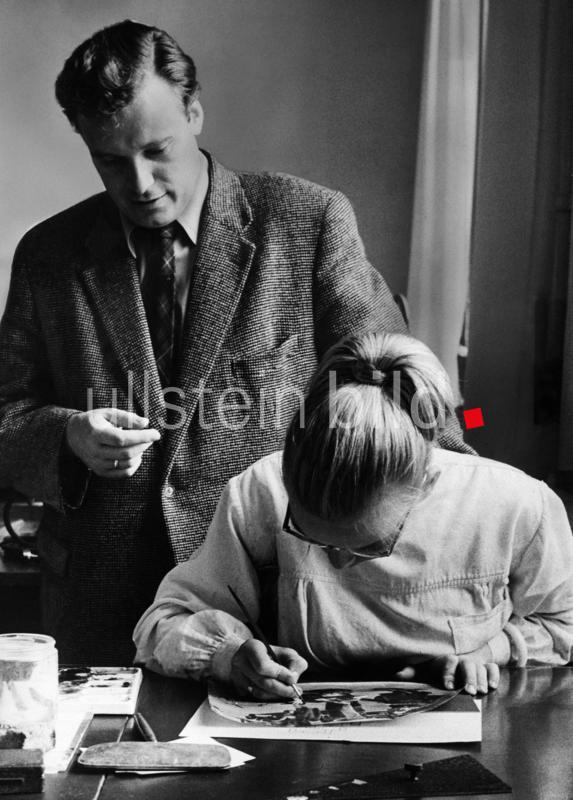

This is a very interesting topic! Press photography is a particularly exciting chapter with regard to used and "violated" images. After all, press photos were not works of art in their creation, but illustrations for the mass press. Photographers supplied what was needed. Retouching, changes to the image detail and similar interventions in the image were commonplace, the rule rather than the exception. In the early days of photojournalism, no photographer would have thought of vetoing such practices of "further processing". He was first and foremost a supplier, and his negotiating position with publishers was also quite small.

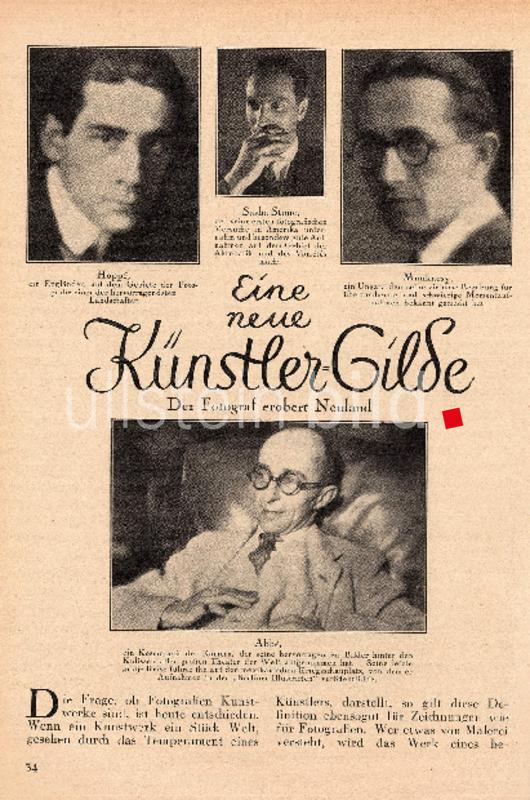

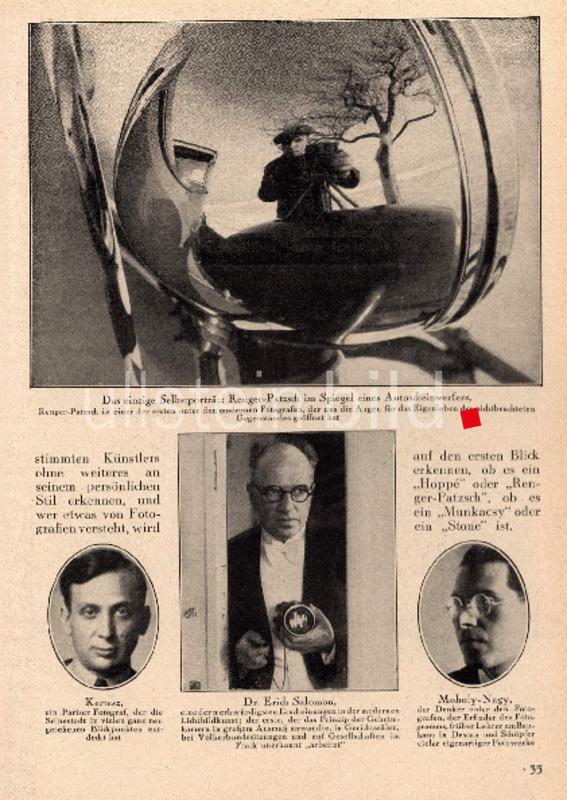

This negotiating position certainly grew with the publishers' "commitment" to their photographers. We are familiar with the article Eine neue Künstlergilde published by Ullstein in 1929 in the magazine UHU. The opening sentence reads: "The question of whether photographs are works of art has been decided today." It introduces well-known photographers who published with Ullstein: Martin Munkácsi, James Abbe, Emil Otto Hoppé, Sasha Stone, Albert Renger-Patzsch, Erich Salomon, André Kertész, László Moholy-Nagy.But when is it documented that photographers negotiated terms of use for their works?

It was only much later, for example with the philosophy of the Magnum agency, that some photographers developed a new self-confidence towards the media. Cartier-Bresson, for example, wanted to see his pictures printed completely unedited and uncropped. But that was the exception.

Looking at the Ullstein photographic collection today, what follows from the view of "violated images"?

In the Ullstein Collection, the traces of the media use of the images are unmistakable. It would be exciting to explicitly address the practices of the photographic craft, which are not afraid to intervene in the photograph, in the form of an exhibition.

You speak of the "entanglement of proximity and distance" as a paradox of "violated images". Does this approach to the works only apply to private photography?

Yes, there are differences. When photos are altered by hand, when body parts are emphasized with a pencil or removed with scissors, when parts of the images are whitewashed, when eyes are highlighted or cut out, then emotions are often involved. On the one hand, these interventions in the picture create distance, they keep the portrayed at a distance. And at the same time, this "violating" is also a practice that creates a special closeness, one comes into contact with the sitter's body, often the act of violation creates an almost intimate closeness.

Are we dealing here with a much more individual approach to the photographs, from which the professional working world of the media differs?

You are right: in private photography, this intervention in images is much more associated with social rituals and emotions than in the much more sober press photography. Here the interventions are often of a "technical" nature, they serve to optimize the image for the reproduction process.

Avant-garde and photography – both themes also came together at Ullstein in the 1920s, essentially motivated by the publications and the history of the publishing house. Are we approaching a higher and more far-reaching sensitization for the subject via the "violated images"?

It is striking that the avant-garde was not afraid to intervene in images. Scissors and glue were part of the everyday tools of the avant-garde movements, for example in the field of photomontage. They cut, separated, combined, glued, omitted, added. Part of the photography of the 1920s is inconceivable without these interventions. It is often overlooked that photomontages were not only used in an art context, but also and above all in the mass press. Many illustrated newspapers of the interwar period printed montaged images.

Here too, the boundaries are fluid – to the benefit of artists and publications.

John Heartfield, who perfected the art of "new seeing with scissors", was not a solitary artist. Many other photographers also worked with scissors and glue – albeit not quite as radically as he did. Newspapers were very open to photomontage. No wonder: the work at the photo editors' light table had to combine texts and images in a suggestive way. What could be more obvious than to intervene in the pictures, remove parts, create vignettes, transfer the text into the picture and much more? The graphically well-designed illustrated newspaper sees the photograph only as raw material that needs to be processed.

What are the consequences for exhibition practice?

"Injured images" are not an outlier in photography, but a genuine part of it. In my opinion, this insight should be incorporated much more strongly into the history of photography and exhibition making. In order to show the processes of image editing, for example, printed newspaper pages should often be placed next to the press images in the archive. Our eyes are often opened when we see the differences.

Thank you very much, Mr. Holzer, for this interview!

The interview was conducted by Dr. Katrin Bomhoff, ullstein bild collection.

First published on April 24, 2024.

In the gallery you can see a selection of images on our topic, the corresponding dossier can be found at ullstein bild.