The photo book for Kurt Safranski 1934

Farewell to Ullstein in Berlin – New York Exile

Interview with Phoebe Kornfeld, lawyer and author of Passionate Publishers – The Founders of the Black Star Photo Agency, New York

_______________________________________________________________

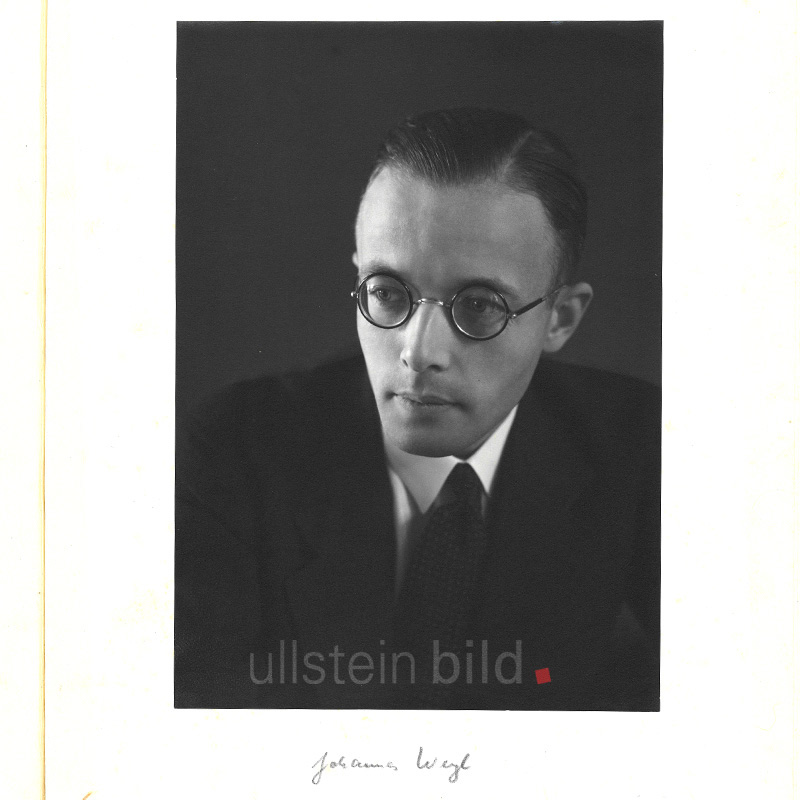

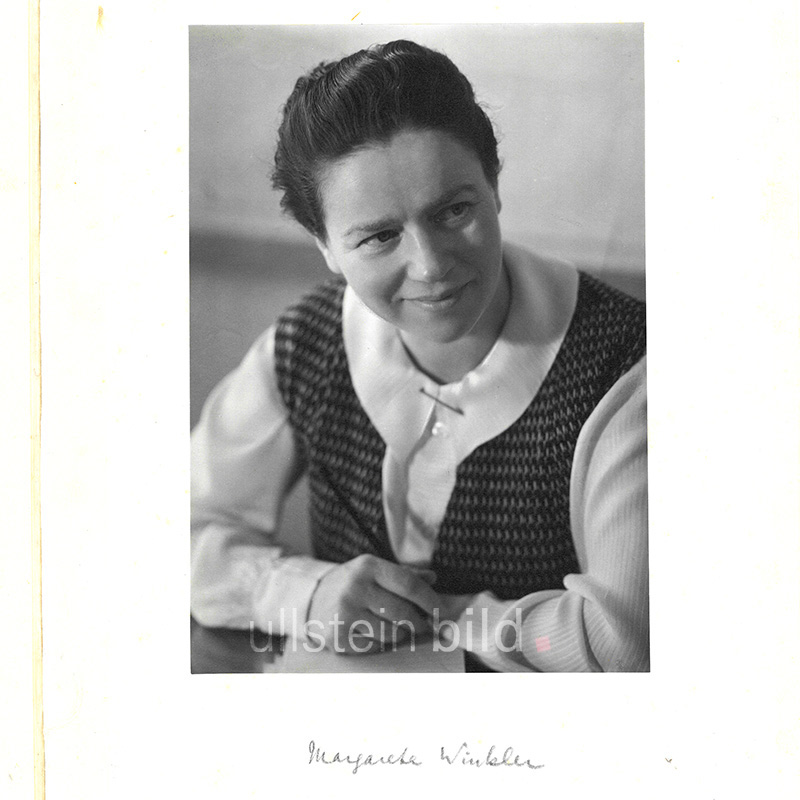

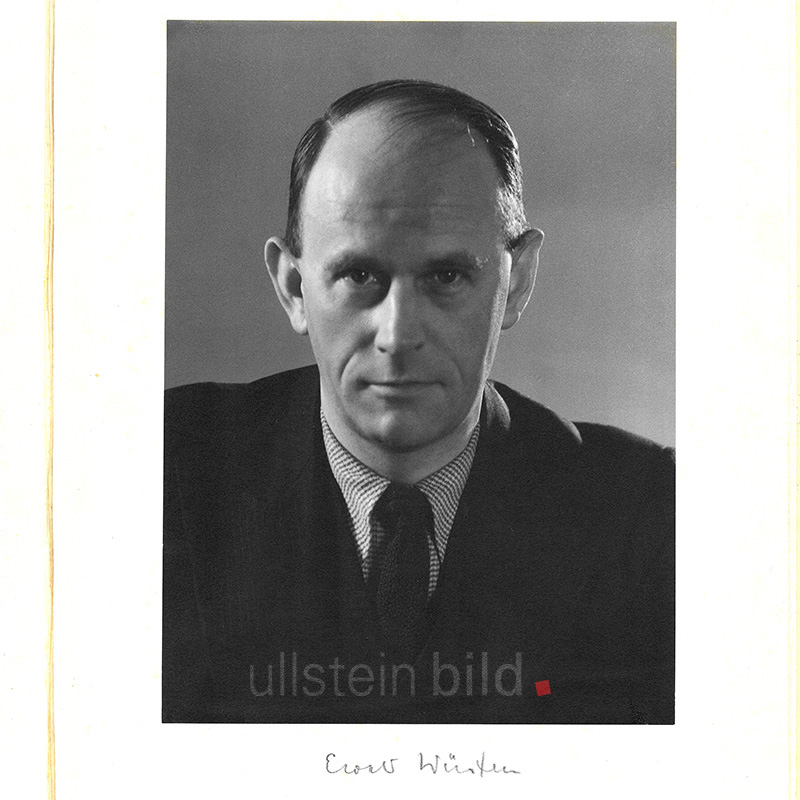

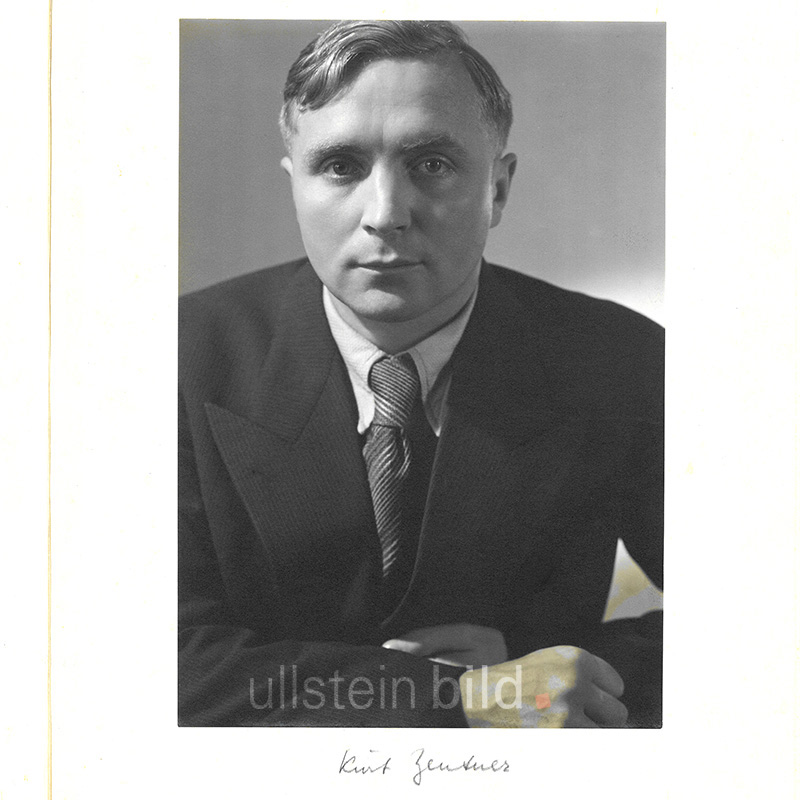

Ms. Kornfeld, on the occasion of the Ullstein exhibition “The Invention of the Press Photography,” we corresponded about a truly extraordinary and unique photo book from the estate of Kurt Safranski (1890-1964), which was kept by his granddaughters in New York. This estate is now kept at the renowned Leo Baeck Institute in New York, while the photo book is located in the corporate archive of Axel Springer SE in Berlin due to its Berlin origins. Kurt Safranski had been artistic director at Ullstein and managing director of the extremely successful Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung since the 1920s. Shortly before he emigrated in 1934 under pressure from political events and left Berlin with his family for New York, a photo book was created: a farewell gift from his colleagues at Ullstein. It contains a total of 23 full-page, glued-in original portrait photographs of his long-time companions, each one signed in pencil in the center below the photograph. These images, the many different handwritings, and above all the introductory text make this unique item a highly valuable testimony to its time. We are permitted to quote the text here faithfully and show it in the image gallery below, followed by all the portrait photographs from the book:

"Dear Mr. Szafranski!

Is there still a little space left in your picture book collection? Give it to this little book! Whenever you open it, it will bring you greetings and best wishes from those who will miss you very much. All those who have witnessed your work closely feel the full weight of the loss suffered by the publishing house, but it is equally difficult for each of us to say goodbye to you personally. Everyone also knows what leaving Ullsteinhaus means for you. You have contributed in many ways to the growth of the company, and your work, in terms of both scope and success, was what one might call a life's work.

But you began it at a young age, and you are leaving it behind with your energy intact! You are capable of taking on a second life's work! We are not merely hoping, but convinced, that this will happen quickly. We only hope that it will be worthy of a man as versatile, as hard-working and energetic, as courageous and responsible, yet as amiable and lovable as you have proven yourself to be in our community!"

How should this farewell text – presumably a collaborative work – be classified? What insights does it give us about the unnamed author(s)?

Dr. Bomhoff, thank you for giving me this opportunity to explore with you the multifaceted significance of the photo album Kurt Safranski received from his colleagues when he left the Ullstein publishing company. On account of his Jewish heritage, Safranski knew as soon as Hitler had seized power in 1933 that the safety and well-being of his family could only be preserved if they left Germany. For Safranski, who along with his Ullstein colleague Kurt Korff was a pioneer in developing the genre of magazine photojournalism in the 1920s, there could have been no better gift from those he was leaving behind than such an album of photos.

When I first read the introductory text in the album, I marveled at how personal it is—so much more like a farewell from family members than one from people "at the office." The acknowledgement of Safranski's appreciation of photo books, the recognition that he had started at Ullstein as a young man who ultimately made unique contributions to the growth of the Ullstein business, and the description of his strong work ethic and endearing personality encapsulate much of his essence.

You have conducted extensive research on Kurt Safranski. What was decisive for his professional work and for his biography of his years in Berlin?

Born in Berlin in 1890, Safranski had trained as a graphic artist with Lucian Bernhard and specialized in creating book covers, posters, cartoons and caricatures. When I realized how little is known about Safranski's own artwork and writings, in an appendix to Passionate Publishers, I catalogued all I could find. Even before his resounding success in 1912 collaborating with Kurt Tucholsky on Rheinsberg. Ein Bilderbuch für Geliebte (Rheinsberg. A Picture Book for Lovers), Safranski had started to create colorful cover art for an Ullstein series of musical scores called Musik für Alle (Music for Everyone), several of which he had retained and are now in the Axel Springer Archive. In parallel with his appreciation for the graphic arts, Safranski had long valued "The Beauty of Old Photographs," as he entitled a piece he wrote for Ullstein's Die Dame magazine in 1920. From his beginning as artist and artistic advisor at Ullstein, Safranski's quite visionary talents led him to become Director of the Ullstein Magazine Division. Along the way, he had served in the 1920s as the initial managing editor of two popular magazines, Der heitere Fridolin (The Carefree Fridolin) and Uhu, both of which included photos in story layouts. And then, of course, Safranski's collaboration with Kurt Korff to develop photojournalism in Die Berliner Illustrirte (The Berlin Illustrated Magazine) is now legendary.

What else went through your mind when you held the photo book in your hands for the first time in New York?

What I did not know when I first found the photo album we are talking about is the extent of the naïvité in the introductory text regarding the likelihood that Safranski, then forty-three years of age, would be able to further his accomplishments and repeat his success when he left Ullstein. It is true that Safranski and his fellow refugee-émigré partners Ernest Mayer and Kurt Kornfeld who founded the Black Star Publishing Company in 1935 made significant contributions to the development of photojournalism in the US. Their combined expertise contributed to the successful launch of Life in 1936 and to innumerable published photos and photo stories in magazines such as Time, Look, National Geographic, The Saturday Evening Post, The New York Times Sunday Magazine and Parade, as well as in others internationally. All three men were grateful to have found a new lease on life in exile when so many others could not.

However, during the course of my research, I started to develop the picture that Safranski would have liked to have been a senior executive in a US magazine publishing company, as, for example, when he took what he knew to be an underpaid position with the Hearst magazine division when he fled Germany. Ultimately, my impressions were confirmed when I found in the Safranski family's archive, which is now at the Leo Baeck Institute in Manhattan, Kurt Safranski's own evaluation of his professional life in exile. In a letter written in 1955, Safranski recapped his work at Ullstein as a magazine publisher and Director of Ullstein's Magazine Division and said that in the US, he had never been able to practice his actual profession but for many years had been procuring and selling photographs, which he deemed to be a far cry from his publishing activities.

The individual portraits in this photo book are neither signed nor labeled, yet they largely speak a common language. They may date back to the work done at the Ullstein photographic studio in Berlin, which we know today as the Ullstein photographic collection, an independent image author with a stamp print on the back of the original photographs. What do you conclude from the images?

In 1942, Kurt Safranski wrote a letter to Henry Luce, cofounder and head of Time Inc., reminding him of their meeting in 1935 with Kurt Korff when Safranski presented a mock-up, a "dummy" for a new general interest weekly illustrated that inspired Luce to proceed with a project that resulted in the iconic Life magazine. Safranski praised all that Luce and his team had accomplished with Life since its launch in 1936 but proposed that even more could be done. He thought that pictures could be used to do more than help people "see" the world. He thought that especially in the editorial pages, pictures could be used to "convey ideas," if one added to the semantics of words "the semantics of pictures." A copy of the letter, along with Safranski's notes for a lecture he gave three years later on "non-verbal maps" at a semantics symposium are in the Safranski archive. It is obvious that the subject was important to Safranski, who cofounded and directed the New York Society for General Semantics.

I think we can view the selection of portraits in the photo book we are discussing here as just such a "non-verbal map." The subjects include secretaries, editors, artists, authors, journalists and senior managers. But the portraits are arranged alphabetically by the individuals' last names, not by job title or in order of seniority. It would interest me to map the locations of their offices in the Ullstein buildings to understand the path Safranski would have taken to see each of them during his years at the company, but I have not yet tried to do that.

Are you also assuming that the photographs are produced and compiled on a very individual basis?

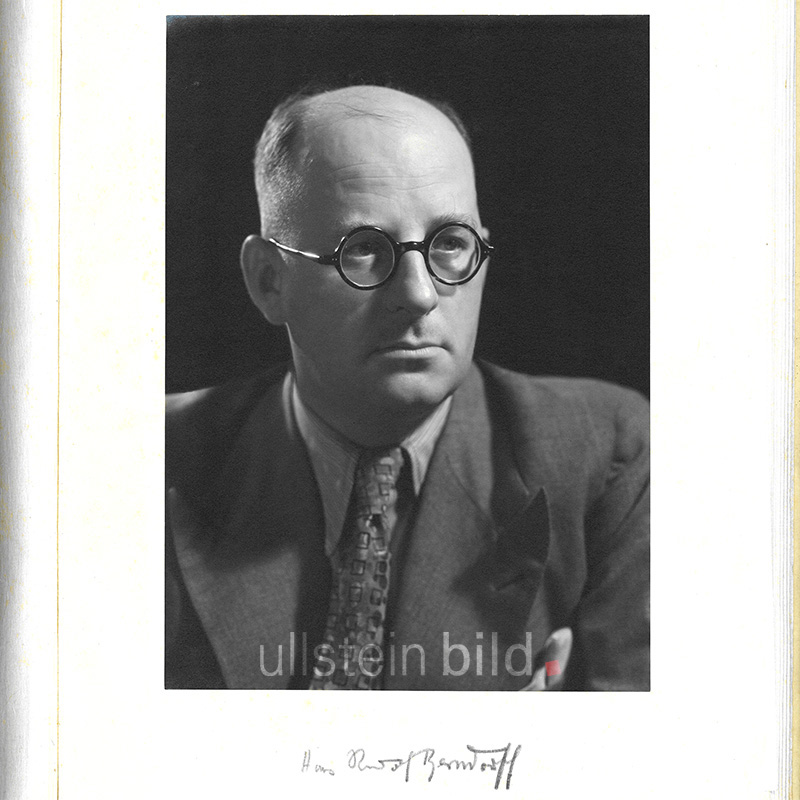

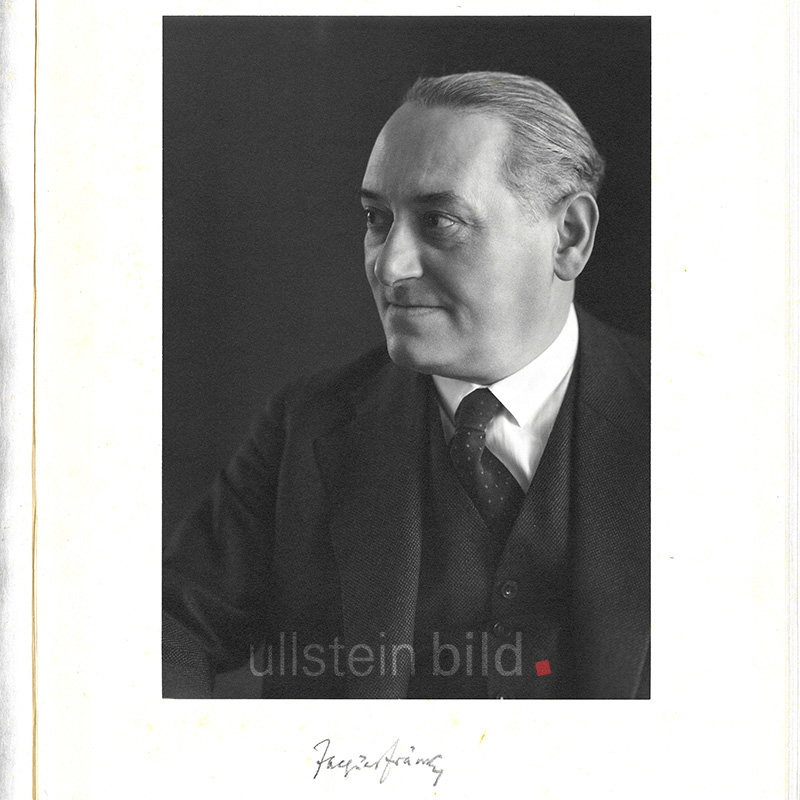

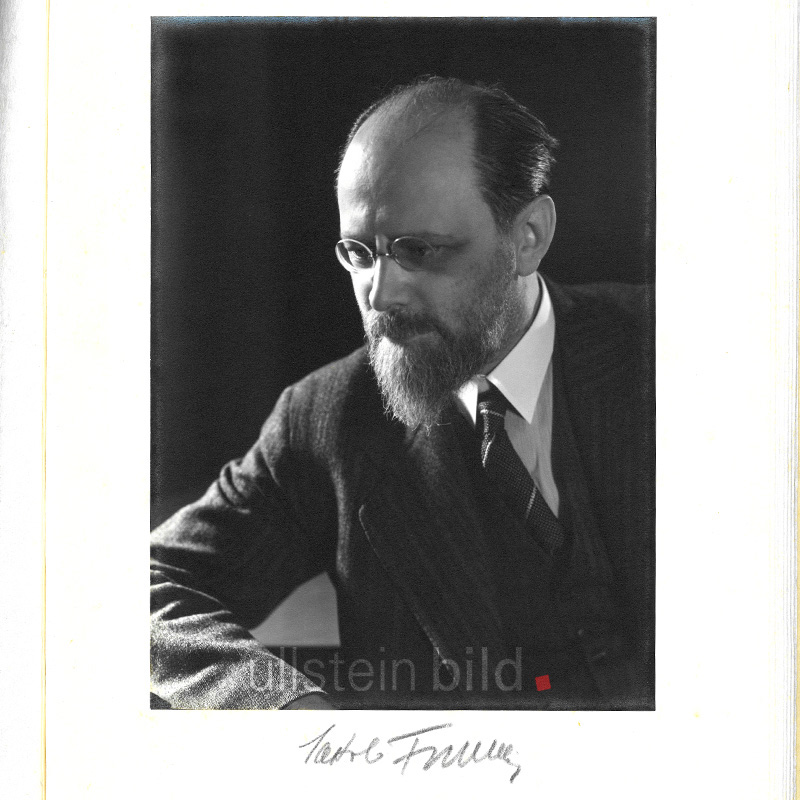

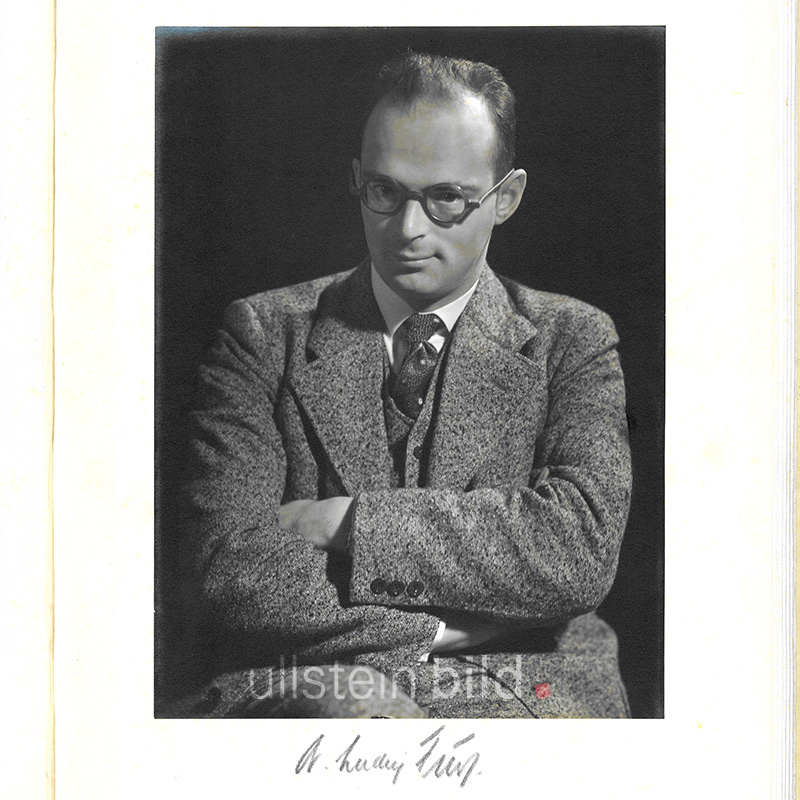

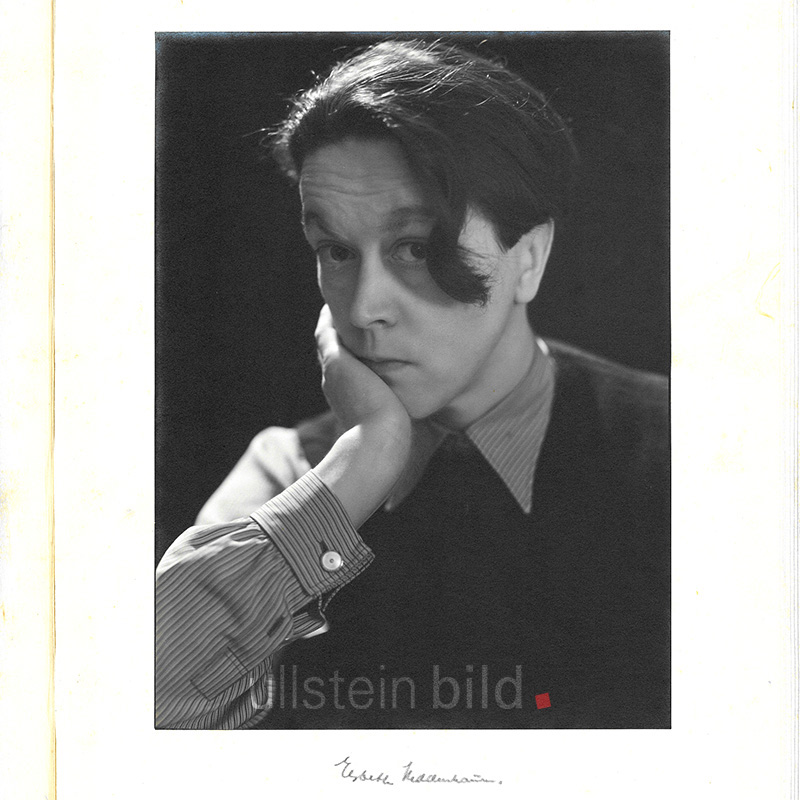

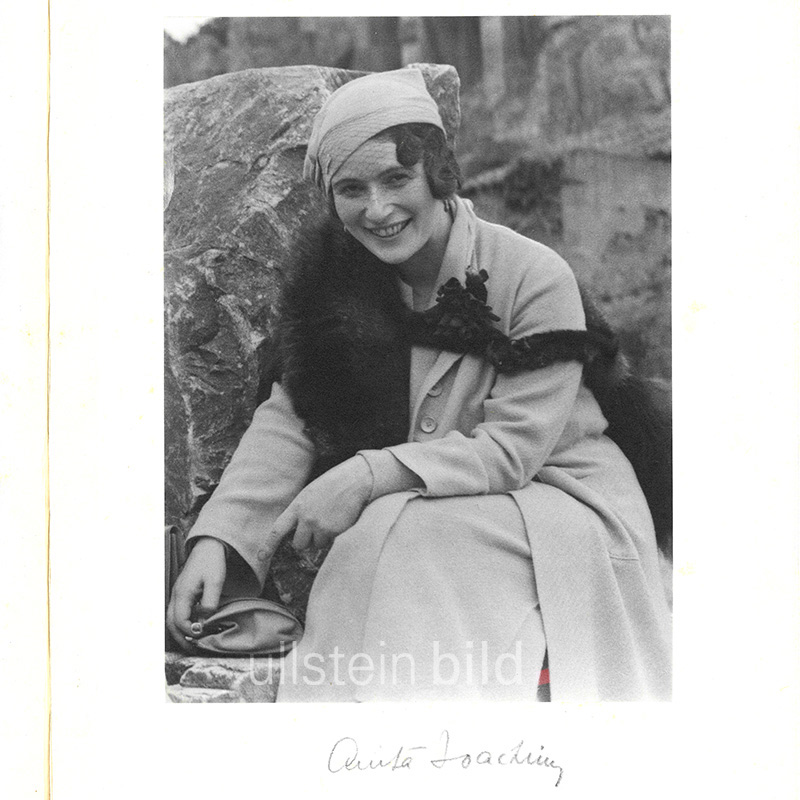

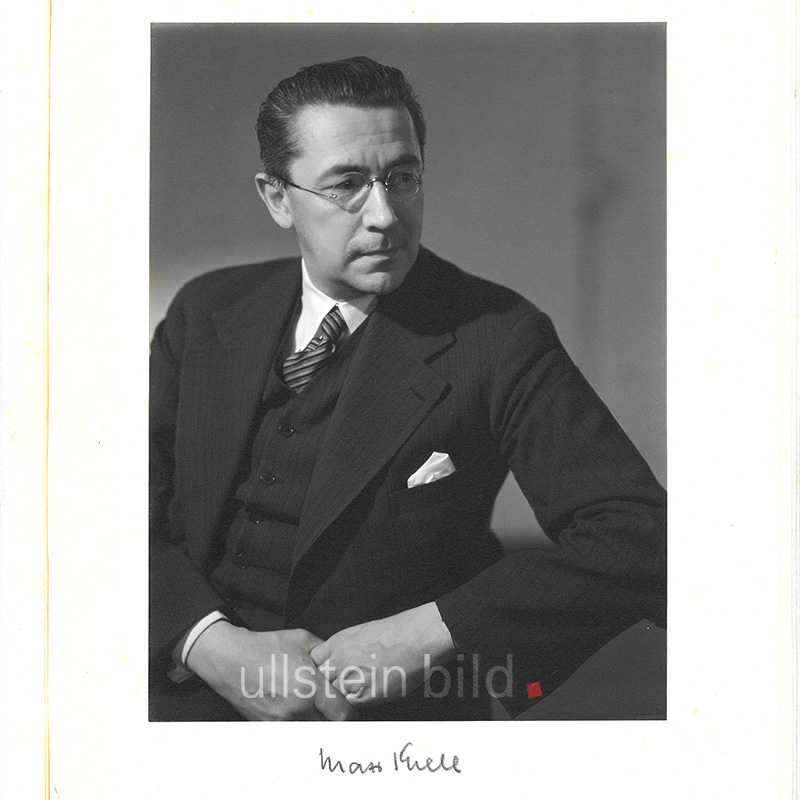

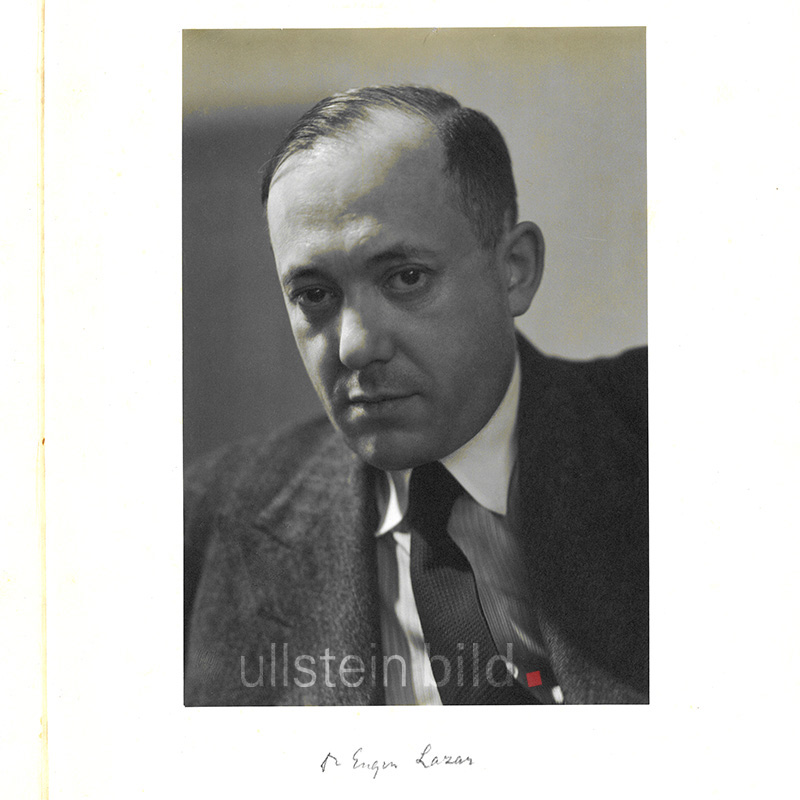

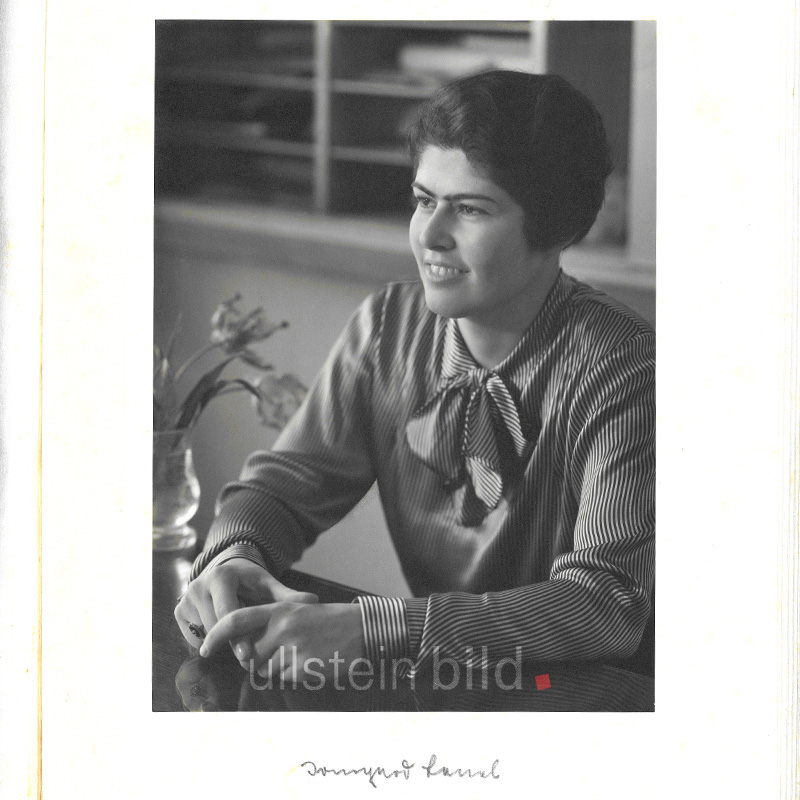

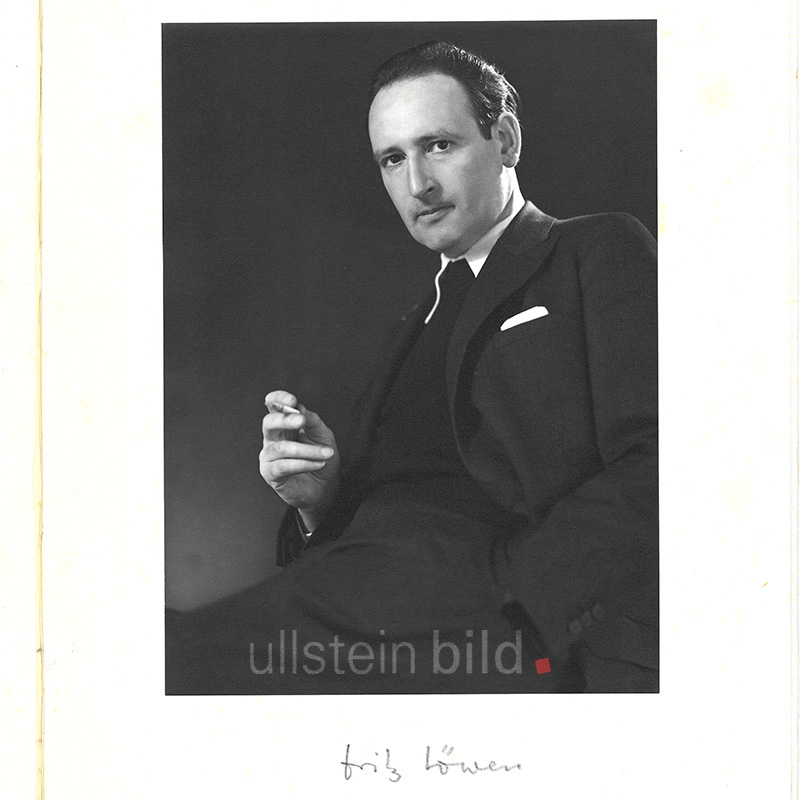

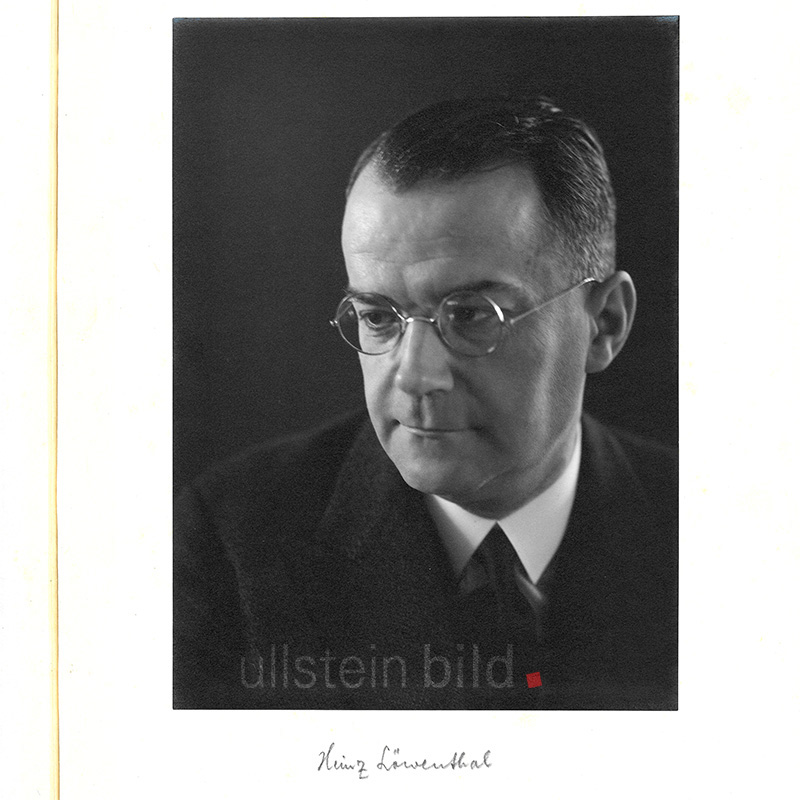

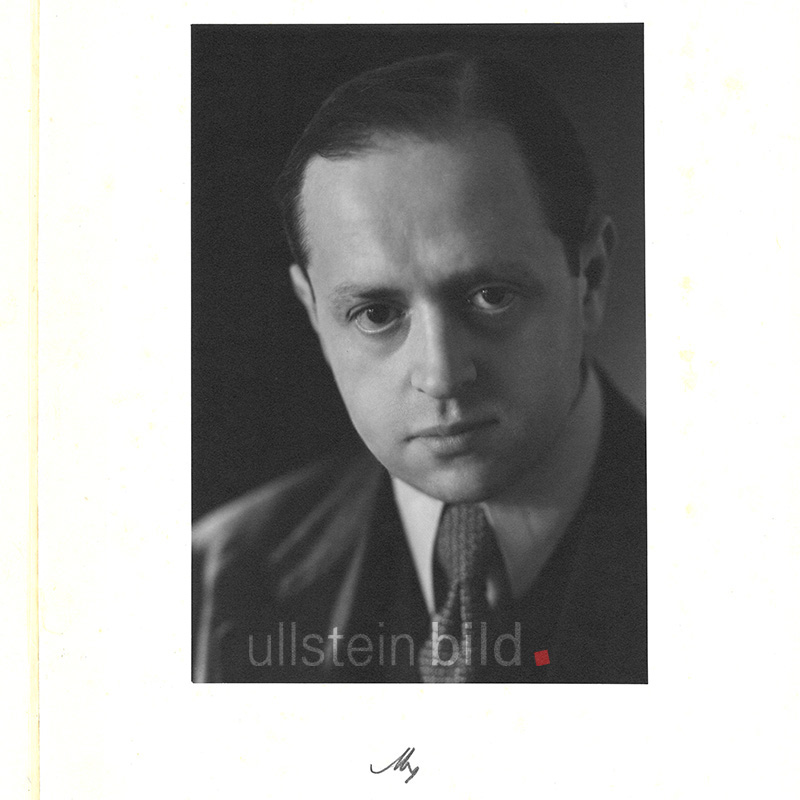

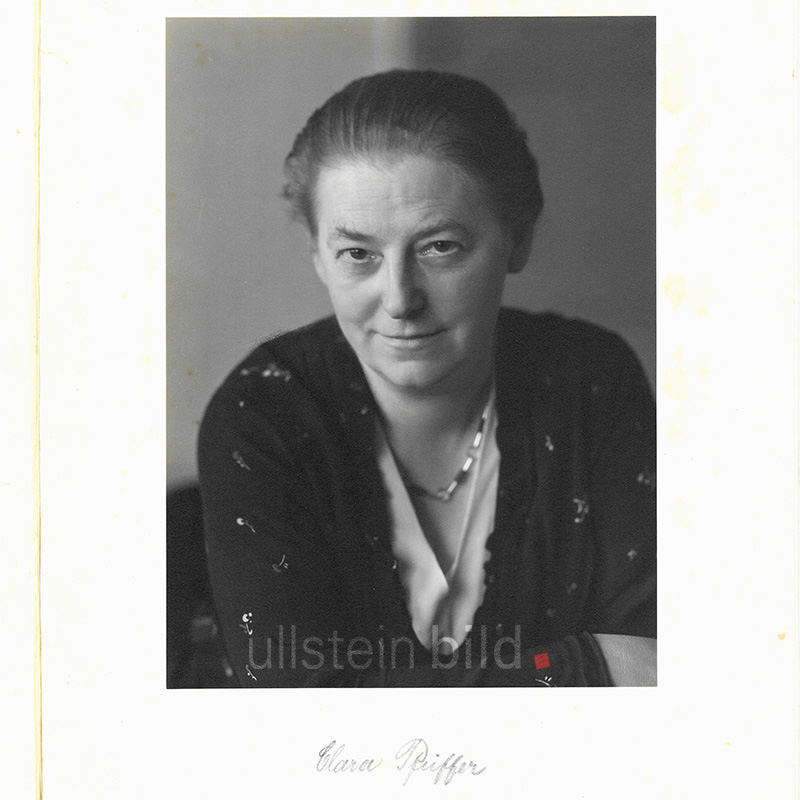

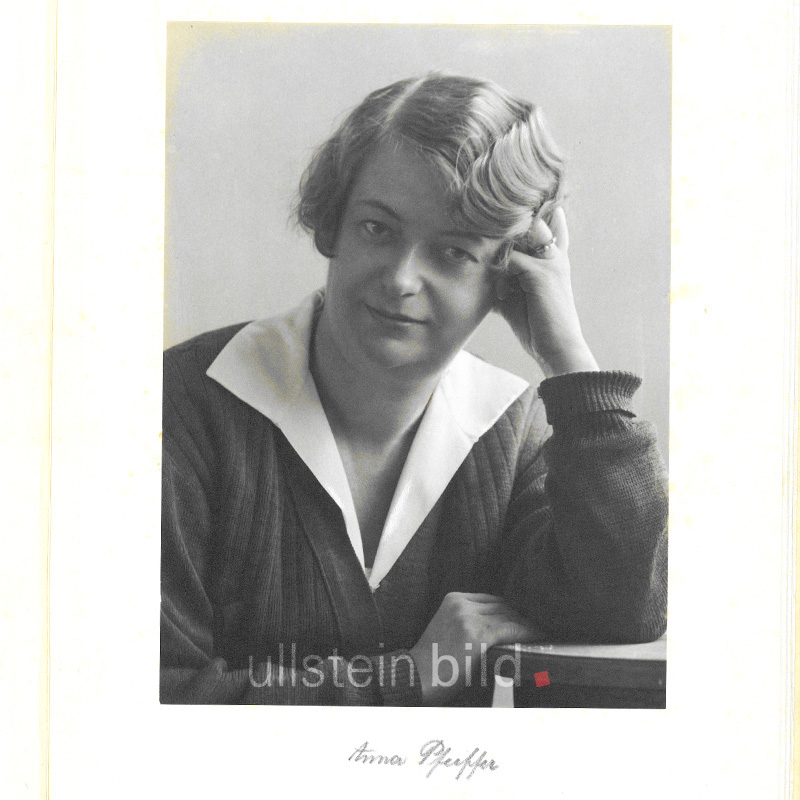

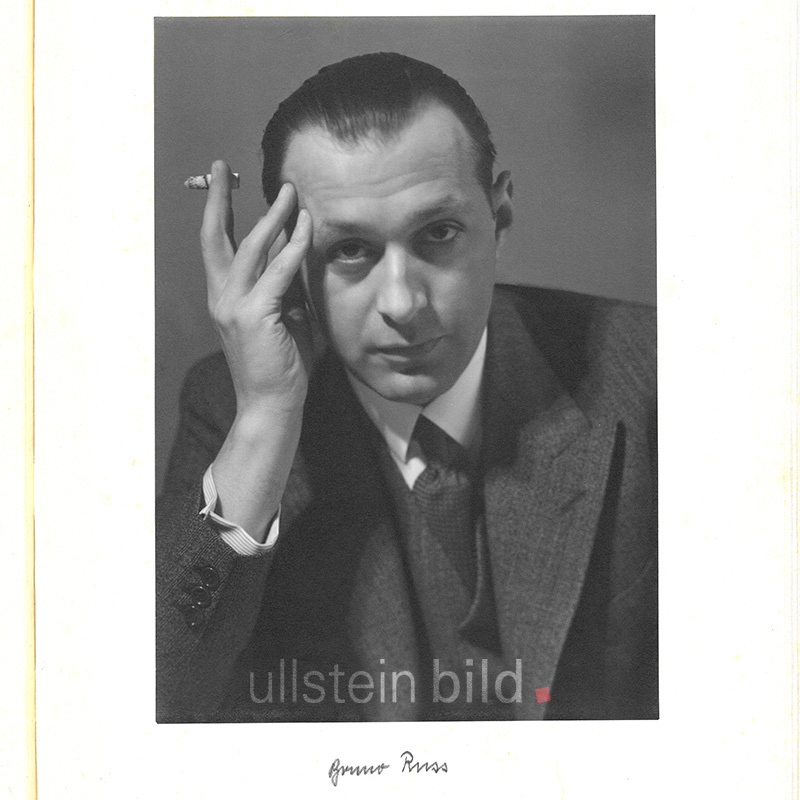

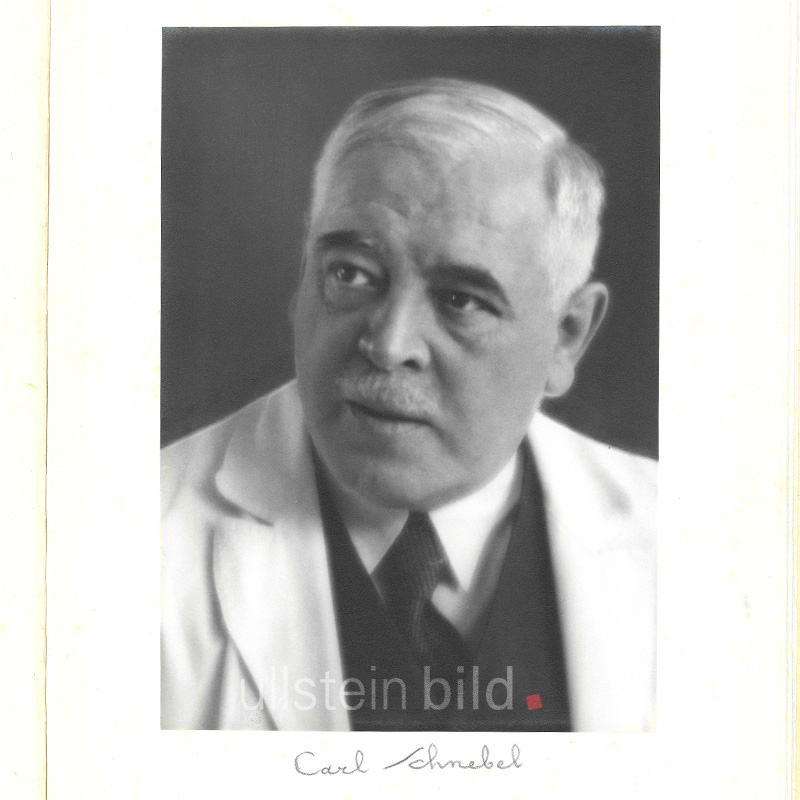

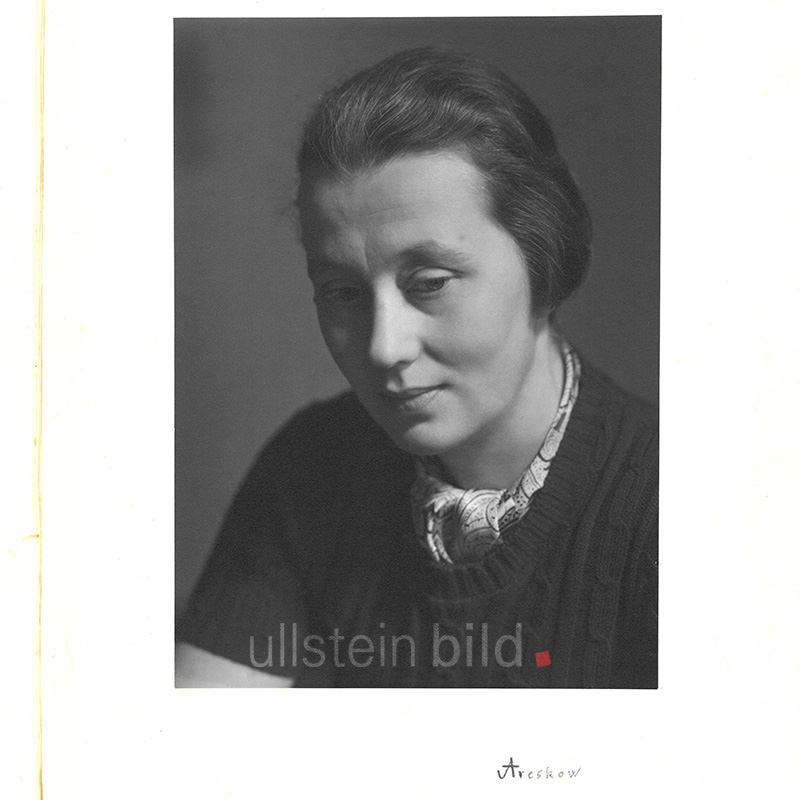

Yes, these are by no means standardized photos for the company's annual report. Quite the contrary, each subject seems to have faced a photographer or selected a photo knowing that this was an opportunity to send a message to Kurt Safranski. When I look at each photo one after the other, I see various thoughts being projected by the subjects, including "remember the good times" (author Anita Joachim, editor Irmgard Lenel, and secretary Margarete Winkler)," don't forget us," (editor Dr. Ludwig Fürst, secretarial sisters Anna and Clara Pfeiffer, senior artistic director Carl Schnebel) to "what is going to become of us?" (author Jacques Fränkel/Ludwig Reve, editor Jakob Frumkin, head of the photography department Elsbeth Heddenhausen, fiction editor Max Krell, author Dr. Eugen Lazar, editor My/Wilhelm Meyer, head of advertising Bruno Russ)."

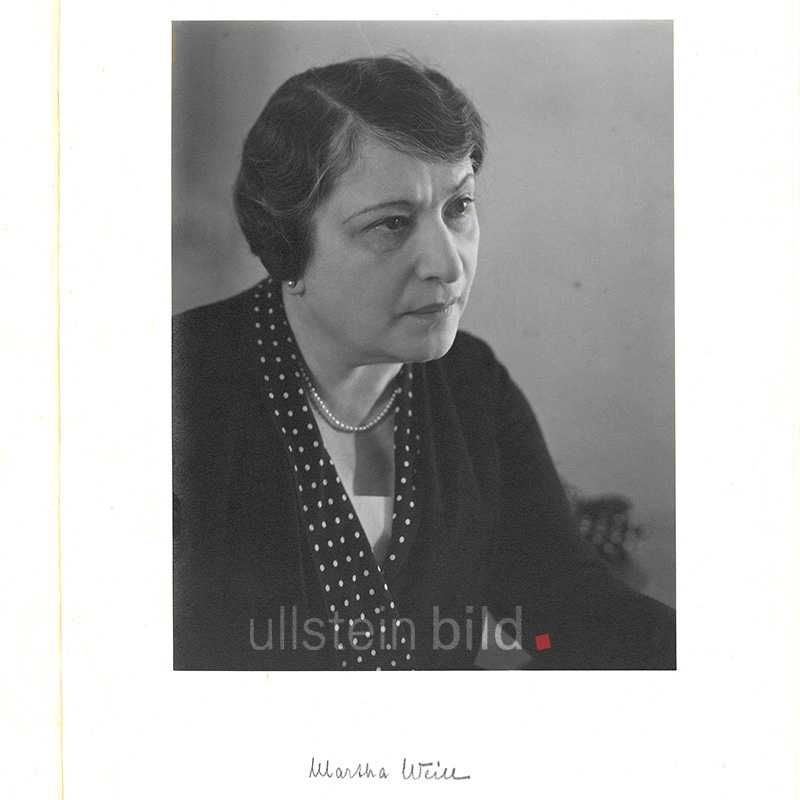

Finally, the portraits cause me to think about another kind of map, namely, tracing the paths of each of these individuals in the years that followed. Thus far I know that several emigrated to the US — Jakob Frumkin via France and Lisbon, Anita Joachim via Switzerland and Portugal, Irmgard Lenel from Berlin, Martha Weill via Buenos Aeres where she had lived with her family as a young woman early in the twentieth century and Otto Zoff via Italy, France and Portugal. Dr. Ludwig Fürst fled to Vienna and then to England, which also became the refuge for Fritz Löwen who changed his name to Lucien Lowen. Jacques Fränkel died in prison Prague in May 1945, but I have not yet established exactly where he spent the war years. My/Wilhelm Meyer died in 1942 in the Berlin apartment he was living in at Bleibtreustraße 20 with his wife, who managed to survive the war with false papers and the help of two friends. Max Krell, not Jewish, but apparently not comfortable in Nazi Germany, emigrated to Florence.

How did Safranski's subsequent meetings with his Berlin colleagues unfold?

It is notable that several of those from the photo album who survived the war remained in contact with Kurt Safranski as did other of his former Ullstein colleagues. I know this from correspondence in the Safranski archive and from a diary Safranski kept in 1953 when he returned to Berlin to work with the Ullsteins on creating a new illustrated insert for Sunday papers. For the purposes of that project he traveled extensively throughout Germany and was several times in England. Just days before Safranski was to set sail from New York in January, he met with Otto Zoff, who was concerned about whether his application for US citizenship would be granted. Once in Germany, Safranski saw Ewald Wüsten in Cologne in February, Johannes Weyl and his wife in Konstanz in March, the Pfeiffer sisters in Berlin later that month, Elsbeth Heddenhausen in April in Berlin and Barbara von Treskow the next day in Hamburg. In May, he saw Ludwig Fürst in London. By 1953, Safranski was already quite unwell with heart problems that led to a serious health crisis four years later. That he nonetheless invested such time and energy into cultivating these personal relationships is a strong confirmation of the description of his character contained in the introductory text to the photo album.

Among those portrayed are close and important companions such as Carl Schnebel (1874-1942), a member of the artistic advisory board at Ullstein. Together with Kurt Safranski, he was responsible for collaborating with influential photographers of their time, thereby contributing to the success of pioneering Ullstein titles such as Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung and Die Dame. Which portraits in the photo book are exemplary and therefore of particular interest?

If I look at these twenty-three photos as though there were no signatures accompanying them, three in particular stand out to me — those of Carl Schnebel, Elsbeth Heddenhausen and Anita Joachim. But there are signatures beneath the photos, and so I naturally want to know more about the individuals and how closely their portrait in this album reflects their personality. So, I would like to make a few comments regarding both the distinctiveness of the three photos and my thoughts about what they project based on what I know so far about Schnebel, Heddenhausen and Joachim.

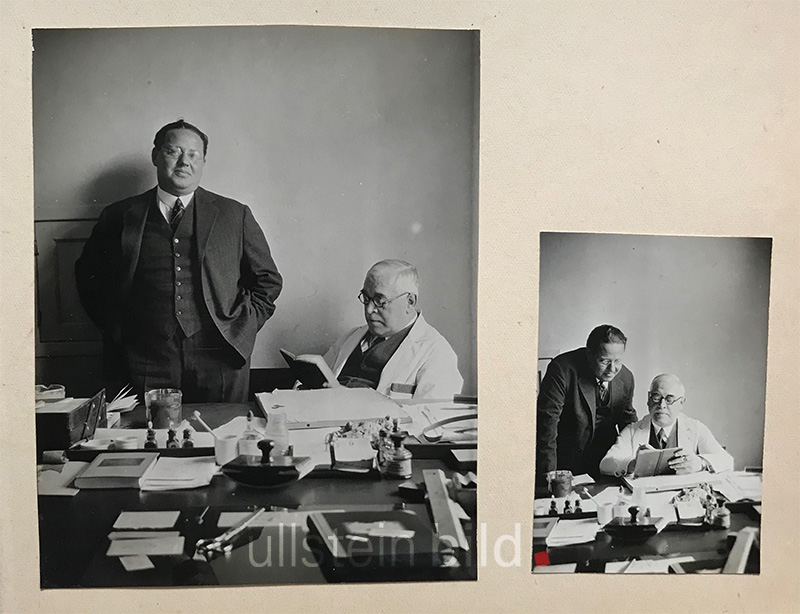

The wonderful photo of Carl Schnebel wearing his white overcoat signifying his profession as an artist, depicts a man nonetheless solid, strong, decisive, but also deep-hearted. His eyes seem to be speaking directly to Safranski. It is interesting that photos of the two men in Schnebel's Ullstein office that are in the Safranski archive show Schnebel wearing his white coat, protecting his suit jacket sleeves from the inks on his desk, but wearing thick eyeglasses for his work. That he removed the glasses for this photo in the Safranski album makes it all the more a personal rather than a professional gift. Finally, on the basis of my impressions of Schnebel from this photo, it did not surprise me to learn that one of the first things he did upon his retirement from Ullstein in 1937 was to travel to the US to visit a son who had emigrated early in the twentieth century and become a US citizen. His son lived in Hoboken, New Jersey, close enough to Manhattan that Carl Schnebel could easily have spent time with Kurt Safranski while he was there. I like to think he did.

The other two photos that particularly draw me in are those of Elsbeth Heddenhausen and Anita Joachim, where I see projections of the Weimar era "New Woman" in Berlin. These are two working women willing to be themselves in very different styles.

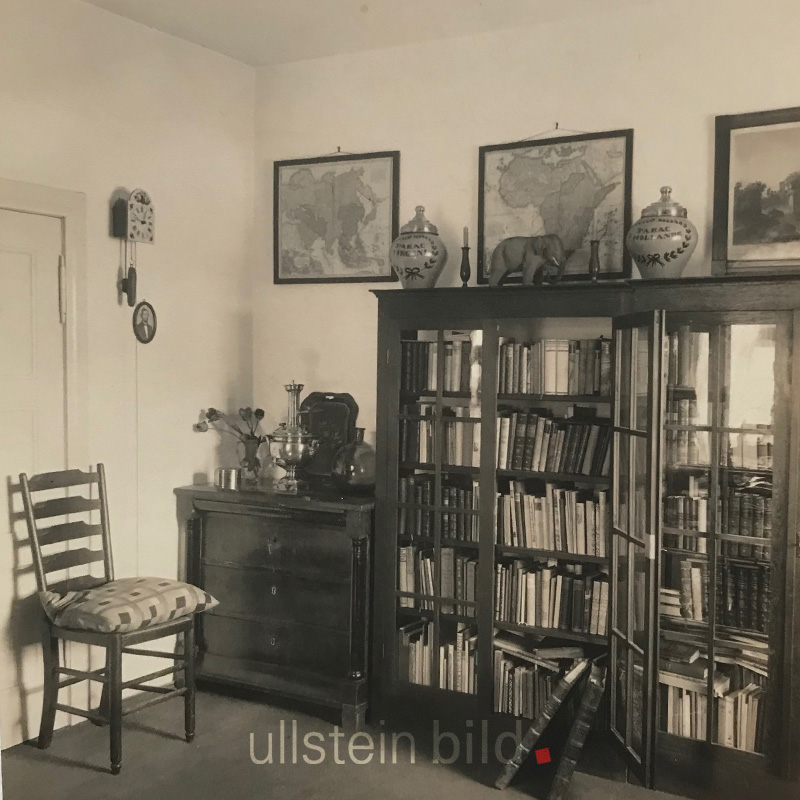

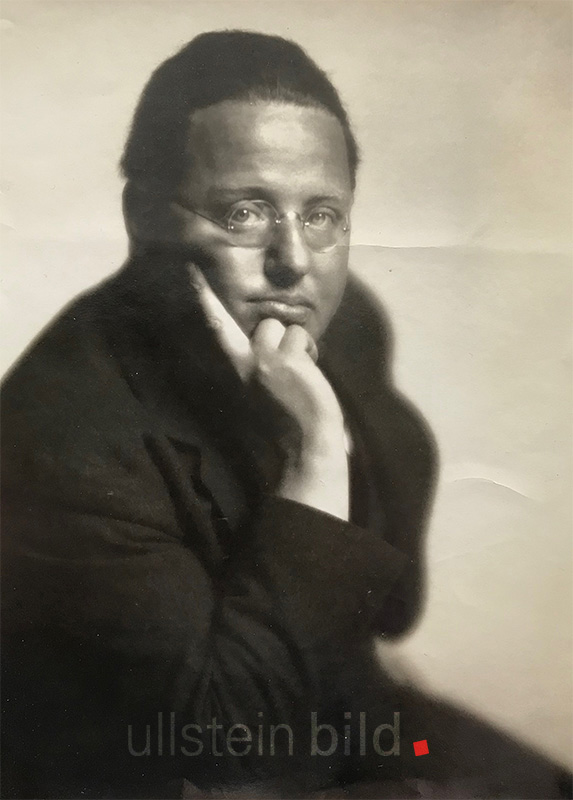

Born in 1897, in Nendorf, Stolzenau, in Lower Saxony, Heddenhausen studied photography at the renowned Lette Association and worked in a studio called Heddenhausen & Weiß. It seems to me that she would more often have been behind the camera and in the dark room, but at Ullstein she became head of the photography department, implying that her interpersonal skills were as strong as her technical abilities. The photo itself, certainly intentionally, has the most interesting use of light and shadow of any of the portraits in the album. The pose also strikes me, not just because I wish I could ask her what she was thinking at the time, but because Safranski himself sits similarly in a photo by Bucovich in the Safranski archive, perhaps shot on the same day as Safranski's photo in Ullstein's commemorative book 50 Jahre Ullstein. 1877-1927 (Fifty Years of Ullstein. 1877-1927). I do not know when Heddenhausen and Safranski first met, but she took photographs in his home in the 1920s and he respected her work enough to have retained a copy of a 1937 book for which she photographed houses. In 1953 when he went to see her in Berlin, it was to pick up photos, indicating a continued esteem for her and her work.

The author Anita Joachim, on the other hand, chose to include a photo of herself rather glamorously attired and coiffed, in an outdoor setting leaning against a massive solid rock formation. The broad smile on her face and the joyous expression in her eyes beaming directly into the camera project her positive and light-spirited personality that is reflected in her writing, a good deal of which is commentary about and for women across cultures. Born Anita Daniel in 1892 in what is today Romania and educated internationally and multilingually, at Ullstein she wrote for Die Dame and Uhu, two of the magazines within Safranski's purview. I think she wished to present Safranski with a photo that would make him smile and think of the good times they had shared. After emigrating to the US, she continued to write in English, for The New York Times, for example, and also in German. She lived on Manhattan's Upper East Side, so I would not be surprised to learn that she and Safranski remained in contact, but I have no proof of that at the moment.

Do you think anyone is missing from this photo book?

Yes, it seems to me that as wonderful as this album is, there are two important people missing: Kurt Korff and Kurt Safranski himself. I think that to come nearer to Safranski's objective of using pictures to convey ideas, to make people think, it is necessary to see also Kurt Safranski and his close collaborator Kurt Korff, who had already left Ullstein in 1933 and thus was not in the album. To this end, I have received permission from the James Abbe Archive to include here the only photo I have found of Safranski and Korff together, taken by Abbe in Manhattan once Safranski had lured Korff there. Interestingly, it was Safranski who signed Abbe's press pass for 1932 on behalf of the Ullstein Bilderzentrale when Abbe worked in Berlin.

The estate of your grandfather Kurt Kornfeld (1887-1967), a Berlin publisher and co-founder of the Black Star photo agency in New York in 1935, has also been part of the extensive and rich collection at the Leo Baeck Institute since 2024. What did this step mean for you?

Well, Dr. Bomhoff, on the one hand this question is very personal. Because of the tremendous influence my grandfather had on my life when I was young, I was deeply moved when I found the small archive of his materials from Germany in the attic of my parents' home in 2011. I am grateful that I was able to take early retirement and then had the time to work with the archive intensively for the purpose of writing Passionate Publishers. Once that was completed, I consulted with my sisters, and we thought that our priorities regarding the materials should be preservation and accessibility and agreed that it would be good for Kurt Kornfeld's archive to be housed in the same place as Kurt Safranski's at the Leo Baeck Institute.

On the other hand, you know how much I value the lessons that can be learned from history. Passionate Publishers includes biographies of Mayer, Safranski and Kornfeld as well as Black Star during the founders' first generation leadership of its business from 1935 through 1963. To maintain balance in the book, I could not possibly cover all there is to know about any of those four subjects, and I am certain there is more that can be said about them. Only through accessibility to original documents such as those in the Kornfeld and Safranski archives now at Leo Baeck can we create and refine verbal and non-verbal maps of the personal and professional lives of these men before and after their journeys into exile.

Thank you very much for this interview, Ms. Kornfeld!

Questions: Dr. Katrin Bomhoff, ullstein bild collection

First published on September 5, 2025.

In the gallery, you can see the pictures from The Photo book for Kurt Safranski 1934 and the following additional photographs, which we are able to show here thanks to Phoebe Kornfeld and with the permission of the James Abbe Archive and the Kurt Safranski Archive:

- James Abbe: Kurt Safranski and Kurt Korff in Manhattan, New York, between 1934 and 1937, ©James Abbe Archive 2020

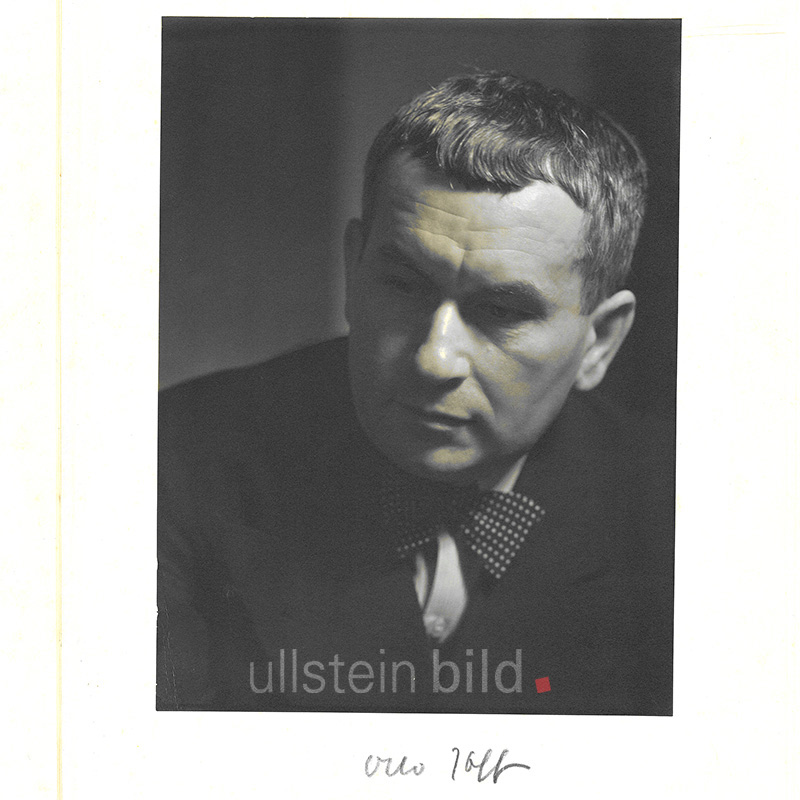

- Mario von Bucovich: Portrait of Kurt Safranski, around 1930, ©Kurt Safranski Archive

- Heddenhausen & Weiß: Kurt Safranski's residence in Berlin-Wilmersdorf, Hanauer Str. 19e, interior view of living room, 1920s, ©Kurt Safranski Archive

- NN: Kurt Safranski and Carl Schnebel at Ullstein Verlag in Berlin, 1920s, ©Kurt Safranski Archive.

You can find a photo dossier on this topic at ullstein bild.

The Photo book for Kurt Safranski contains original portrait photographs of:

Hans Rudolf Berndorff, author and editor at Ullstein

Jacques Fränkel, author and editor at Ullstein

Jacob Frumkin, editor at Ullstein

Dr. Ludwig Fürst, author and editor at Ullstein

Elsbeth Heddenhausen, photographer and head of the photo studio at Ullstein

Anita Joachim, author and editor at Ullstein

Max Krell, author, theater critic, head of literary editing and fiction department at Ullstein

Dr. Eugen Lazar, author and editor at Ullstein

Irmgard Lenel, editor at Ullstein

Fritz Löwen, graphic artist, illustrator at Ullstein

Heinz Löwenthal, commercial manager at Ullstein

My (Wilhelm Meyer), author and editor at Ullstein

Clara Pfeiffer, secretary at Ullstein

Anna Pfeiffer, secretary at Ullstein

Bruno Russ, advertising and publishing director at Ullstein

Carl Schnebel, draftsman, illustrator, artistic director at Ullstein

Barbara von Treskow, author and editor at Ullstein

Martha Weill, editor at Ullstein

Johannes Weyl, publishing director, head of magazine publishing at Ullstein

Margarete Winkler, secretary at Ullstein

Dr. Ewald Wüsten, editor at Ullstein

Kurt Zentner, editor, managing editor, and picture editor at Ullstein

Otto Zoff, author and editor at Ullstein