Proclamation of the German Republic 1918

Interview with Dr. Ludger Derenthal, Head of the Photography Collection of the Kunstbibliothek - Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, on the photograph Philipp Scheidemann on the balcony of the Reichstag building on November 9, 1918, photographed by Erich Greiser, ullstein bild collection

_______________________________________________________________________

Mr. Derenthal, the subject of the photographs of the proclamation by Philipp Scheidemann on November 9, 1918 in Berlin occupies us very reliably every year in connection with the commemoration of that day. There many, later photographs of this decisive event in German history in circulation. And they are titled and published very differently, even contradictorily, which means that research is anything but unanimous on the question of the authenticity of photographs.

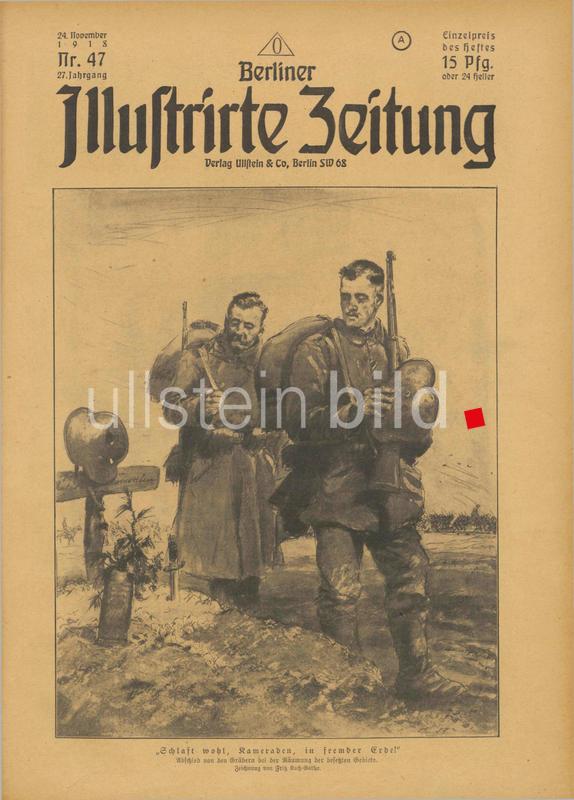

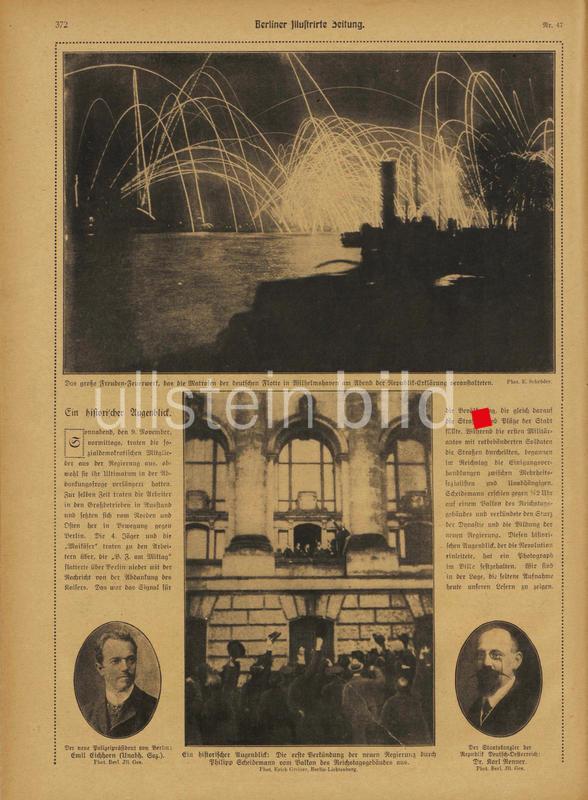

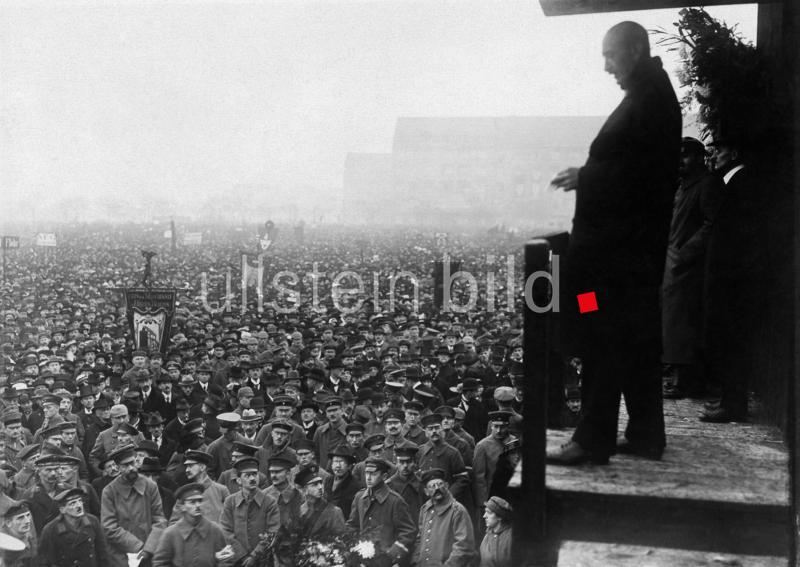

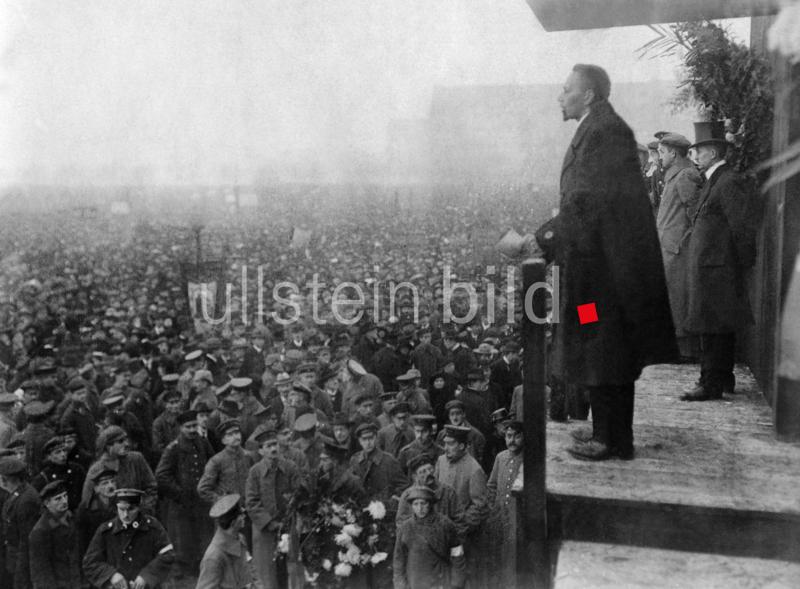

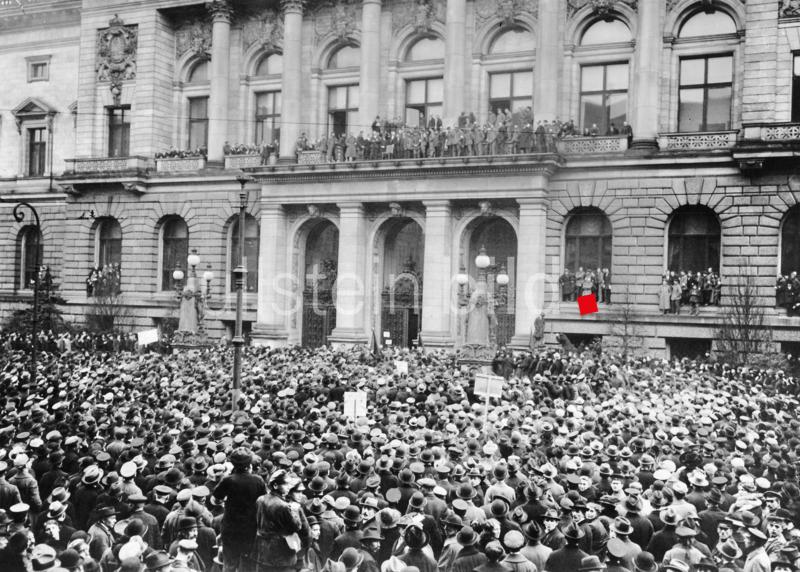

On the occasion of the symposium on the extremely successful exhibition Berlin in the Revolution 1918/1919 at the Museum of Photography, the focus of your lecture was a photograph by a hitherto completely unknown image author named Erich Greiser, which had hardly been examined in detail. The original photograph belongs to the Ullstein photographic collection and was part of the aforementioned exhibition in Berlin. It was first published by Ullstein on November 24, 1918, in the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung No. 47.

Why did you decide to investigate this photograph?

If there were to be a photograph on an important, symbolically charged founding moment of the republic, it would also be able to have an almost iconic significance. The opposition of some historians since the 1990s to the authenticity of the photograph, which in the end was even reflected in an expert opinion by the Scientific Services of the German Bundestag, made it all the more appealing to me to use the methods of the history of photography to investigate the genesis and publication contexts of Erich Greiser's photograph.

What basic results do you arrive at in the context of these new considerations?

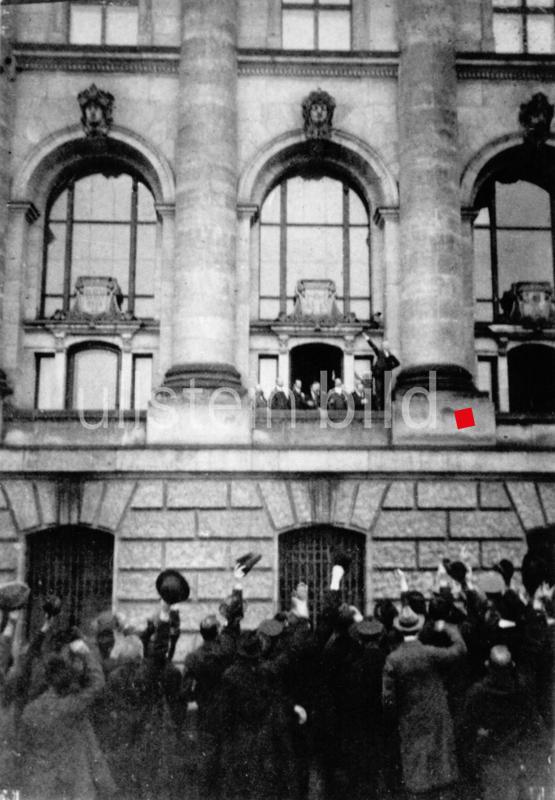

From my point of view, it is indeed the photograph of the historical moment: Scheidemann's appearance on November 9, 1918 was captured with it. Since Erich Greiser photographed with a hand-held camera and it was also a typically gray November day, this photograph did not turn out in the best possible way; it was optimized for printing - as was customary with publications at the time - but the retouching in the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung or for postcards published promptly did not lead to any fundamental falsification. The decisive factor for this thesis is that Ullstein has preserved the print from the negative that has not yet been retouched.

Where exactly do you see contradictions to the previous theories of historians, where do you see similarities?

The authenticity of the photograph has been disputed with numerous arguments, not all of which can be discussed in detail here. Above all, it was claimed that the photograph was a montage of several parts. The proportions were inconsistent: The audience and the speaker on the balcony would not fit together.

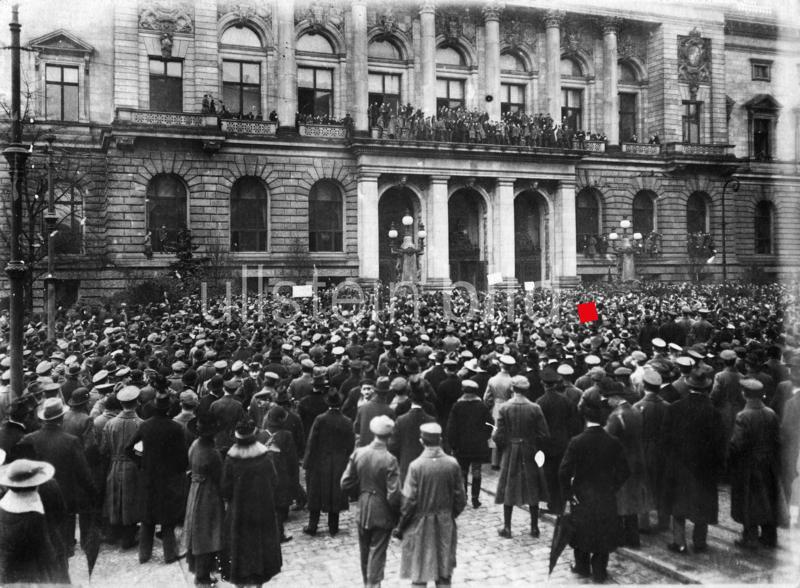

A close examination of the photograph, as well as a visit to the site, allows a reconstruction of the camera's location: the scene is the west front of the Reichstag with Königsplatz in front of it and the Bismarck monument. Scheidemann entered the second balcony to the right of the main portal through the reading room. In front of the balcony, at a distance of about nine meters from the facade, a wide access ramp leads to the portal. The audience stood at a considerable distance from the speaker on the ramp, at the rear parapet of which Erich Greiser also stood with his camera. An important indication of this reconstruction is the front parapet of the ramp, which at one point shows through between the cheering people. The distance between the people on the balcony and the ramp is causal for the proportions in the photograph; the "incoherent proportions" observed by some historians and the height of the balcony not visible in the photograph can thus be explained conclusively. The lighting conditions only allowed the photograph to be taken with a large aperture; because of the resulting lack of depth of field, the demonstrators are captured somewhat more sharply than the people on the balcony.

The second montage suspicion concerns the figure of the speaker, who, compared to the people standing directly behind him, is too tall: I simply cannot see that. It was only in the publications that the speaker's figure was reworked, especially in silhouette, in order to mark him more clearly as the main person. The photo by Erich Greiser, on the other hand, does not offer these unambiguities. In other words, the photograph is technically too poor to be a montage. In its original form, it does not provide sufficient identification possibilities that it should have offered as an iconic image.

How do you assess the decision to publish the photograph in 1918 by Ullstein?

Despite the photographic inadequacies, the editors of the illustrated magazine had recognized the historical value of the photograph, as the caption indicates: "Scheidemann appeared on a balcony of the Reichstag building at about ½ 2 o'clock and announced the fall of the dynasty and the formation of the new government. This historic moment, which ushered in the revolution, was captured on film by a photographer. We are able to show the rare photograph to our readers today." The publication in the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, however, was by no means in a prominent place. It was only placed on page five of the issue, moreover on the 'weaker' left-hand page and in quite a small format (albeit larger than the original print). So one was probably not quite convinced of the symbolic power of the photograph.

Which questions remain unanswered?

Greiser's biography has not yet been sufficiently researched. I was able to find a mechanic of that name living in Lichtenberg in the Berlin address books. I assume that he took the picture as an amateur, realized the importance of his snapshot and initiated the marketing himself by selling it to the Berliner Illustrirte and producing a postcard. It would also be good to know more about the camera he used. I suspect it was a small-format folding camera for roll film, which were already coming on the market en masse during the First World War. However, the evidence is lacking here.

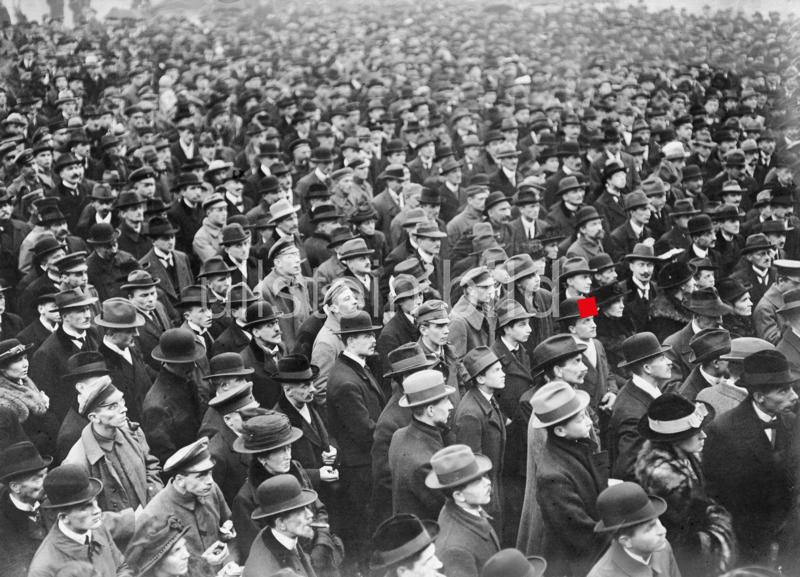

The debate about the authenticity of the photograph itself is still too much in small circles. As long as around every November 9, other photographs and film clips are repeatedly presented in the mass media (and even on stamps), which over the decades have been falsely passed off as images of the event, these overlay the photographic document of the proclamation of the Republic that actually exists. Historians' opinions also differ on the significance of the moment. In this regard, it is at least possible to explain from the perspective of photographic history what important functions the many photographs of the many speakers during the revolution fulfilled in political discourse.

Thank you very much, Mr. Derenthal, for this interview!

The interview was conducted by Dr. Katrin Bomhoff, ullstein bild collection.

First publication January 12th, 2022.

The original photograph by Erich Greiser / ullstein bild collection will be shown again in an exhibition in 2022: Photography in the Weimar Republic in the Peter Behrens Building, LWR Industrial Museum in Oberhausen, from Jan. 23 to May 29, 2022.

In addition to the photograph by Erich Greiser, you can see a selection of other original Ullstein photographs on the subject in the picture gallery; the corresponding dossier can be found at ullstein bild.